Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

As our students create more and more digital products—blog posts, videos, podcasts, e-books—they should be using images to enhance them. Images grab an audience’s attention, they can illustrate key concepts, set a certain tone, and present a more complete understanding of the ideas you’re putting out there.

And the internet is absolutely teeming with images students can grab and use in a matter of seconds. But in most cases, they SHOULD NOT GRAB. Despite the fact that these images are easy to get, using them is probably illegal.

Does this Matter at School?

Is proper image use really a big deal with school projects? If our students are just using images to enhance assignments for class, it might be easy to shrug off the technicalities, since most of these images will never be seen by audiences outside the classroom.

Two things to consider:

- Even if your students are working within a tightly monitored, password-protected, closed online environment, there’s no guarantee that the products they create will always remain private. Proud parents might share their child’s work on social media, a student might place their work in a digital portfolio for future use, and household guests might ultimately view things inside that “closed” environment. So it makes sense to operate under the assumption that all digital products could eventually become public.

- Why not prepare students for the day when these rules will carry more serious consequences? As students move out of school and into professional contexts, being trained in the proper, legal use of images will serve them well.

So in the spirit of complying with the law and preparing the next generation to participate responsibly online, let’s review the different approaches students can take to add images to their written work, blog posts, videos, presentations, and other digital products. We’ll start with the safest, most affordable option.

Disclaimer: I am not a legal expert. My goal is to raise awareness of the complexities of online use of images and get teachers to pass on that awareness to their students. If you find inaccuracies, please point them out and I will make corrections.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Option 1: Make Your Own

If students create their own images, then they own the copyright and can use them without having to pay any money or get permission (unless the photos are of someone else…but we’ll get to that).

ILLUSTRATIONS

When I first started this website, I couldn’t afford to buy nice photos, and I didn’t want to use the same free ones I saw everywhere else online, so despite the fact that my artistic skills are nothing special, I just created my own doodles in MS Paint, like the one shown above. This is a great route to take, because you can get started right away, it’s free, and there’s no copyright to worry about.

Students can create their own illustrations in two ways:

- Handmade: Students can draw or paint an image on paper, create a paper collage, or even build something in 3D like a sculpture, then take a picture of it and use that photo for whatever digital product they are creating.

- Digital: Using simple programs like MS Paint for Windows, Paper by 53 for iOS devices, or web-based tools like Google Drawings, Adobe Spark, Canva, Autodraw, Piktochart, and Sketchpad. On any of these platforms, students can create just about any illustration they can think of, save it as a PNG file, then add it wherever they like.

PHOTOS

Students can take their own digital photos and upload them in a heartbeat, using sites like PicMonkey and Pixlr to edit or enhance them for free. When using photos they take themselves, students should keep the following rules in mind:

- When You Do NOT Need Permission

Although it’s always considerate to ask people permission before you use a photo of them online or in another public space, sometimes it’s not possible, and in these cases, it’s not legally necessary:- If you took the photo at a public event and the photo will be used for journalistic purposes (to simply describe the event, for example)

- If the person is not recognizable in the photo (their face isn’t showing, for example)

- When You DO Need Permission

Have the subject sign a photo release form in person or, if that’s not possible, have them copy the language from a photo release form into an email. If the subject is a minor (under 18 in the U.S.), you need permission from their parent or guardian.- If you’re going to use the photo for commercial purpose (to sell something) or promotional purposes(to promote a product, service, or idea), you need permission from the subject.

- If the photo was taken on private property, even if it is not the subject’s property, you must get permission from the subject to use that photo.

- If you are holding an event, like a festival, party, or concert, and you plan to take photos that you might share with the public, you should get permission from attendees. Event organizers often use crowd release forms at the point of registration: They’ll require attendees to check a box giving permission to use photos of them. Another approach is to hang up crowd release signs at the event itself. Learn more about event release forms in this post from SLR Lounge and this one from Mark Schaefer.

- When You MIGHT Need Permission

- If you are taking photos of students at school, it’s likely that the parents or guardians of those students signed a media release form at the beginning of the school year, giving the school permission to use that student’s image in various non-commercial publications throughout the year. These permissions may also extend to student photographers, as long as you are using the images for school-related projects. Students should check with their teacher and administrator to make sure.

- If the photo contains an image of a store or business logo. Some businesses have rules about using images of their facilities or that prominently feature their logo, so if you are going to be taking photos that will include any kind of business logo or store, get written permission from the business owner first.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Option 2: Use Creative Commons Images

Creative Commons is an organization that has made it much easier for people to share artwork. They have established a set of licenses that artists can place on their work that automatically gives others permission to use that work in their own projects.

A photographer, for example, might add Creative Commons licenses to a collection of her photographs, so that anyone who finds them online knows whether they can be used and what restrictions they have.

If your students want to use images they find online, they should look for images that have Creative Commons licenses. You can learn about all of the licenses here, but the safest bet is to steer students toward pictures that have the two least restrictive licenses:

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

CC0: Creative Commons Zero

This is the least restrictive level, and the one students should look for first. Items marked as CC0 can be used by anyone, for any purpose without having to get permission or give credit to the artist. In other words, an image licensed with CC0 is a public domain image.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

CC BY: Attribution

Items with this license can be used for non-commercial OR commercial purposes, and all the user has to do is give credit to the original artist.

[Both license images above came from Creative Commons and are licensed under CC BY 4.0]

WHERE TO FIND CREATIVE COMMONS IMAGES

Free Stock Photo Sites

These fantastic sites curate free, high-quality images that are all CC0 licensed. Simply search for what you need, download the photos you like, and use them. Unfortunately, many free stock photo sites contain adult content, so unsupervised students should not use them, but if your students are working under adult supervision, they should try these sites. Here are a few good sites that don’t appear to contain inappropriate content:

StockSnap

Good Free Photos

Foodiesfeed (all food-related)

Flickr Commons

Flickr is where thousands of photographers store their photography for public display, and many of these photos have CC0 and CC BY licenses.

Photos for Class

This is a handy search engine for finding school-appropriate images. My only hesitation with recommending this site is that it automatically adds attribution to each photo. Although this could be seen as a good feature, I feel it doesn’t really teach students how to give appropriate attribution, because it does the work for them. Also, students may not always want the added black bar with the attribution information at the bottom of each image, and they may be tempted to simply crop it out, which would defeat the whole purpose.

Google Image Search

Although a Google search will pull up plenty of images students don’t have permission to use, the search can be filtered so that the results only show images that are licensed for re-use. Just be sure to open up the Tools after you search, and check one of the options under “Usage rights” that will remove all of the photos that have not been labeled for some kind of reuse. Checking “Labeled for reuse with modification” should give you images that have the least amount of restrictions.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HOW TO GIVE PROPER ATTRIBUTION

If students use an image that requires attribution, students should simply add a line of text underneath the image providing four pieces of information (Creative Commons recommends using the acronym TASL to remember these):

T = the title of the image

A = the author (or artist)

S = the source (or where it is located online)

L = the license for the image

Ideally, the attribution should be placed fairly close to the image, so that those who view it connect the information to the picture. Here are some examples of properly attributed images:

Online

If you use the image in a blog post or on a website, you can place the attribution in the caption or on a line of text below the image:

Clik here to view.

Blood Orange Shine by Derek Gavey is licensed under CC BY 2.0

In the above attribution, I included the title, “Blood Orange Shine,” the name of the author, Derek Gavey, and the code for the license. Because the image will be displayed online, I can include the location by just hyperlinking the title to URL of the site where the image is stored. I can also hyperlink the author’s name to his page on Flickr, the photo sharing site where the photographer stores his photos, and the name of the license to the license page on the Creative Commons website.

In Print

Because print publications don’t allow hyperlinking, I would need to add the URL information to the attribution:

Blood Orange Shine (https://www.flickr.com/photos/24931020@N02/14995800960/) by Derek Gavey is licensed under CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/)

If doing this right by the photo would make my product look less attractive, I can add the photo credit to the bottom of the page or on a page of photo credits.

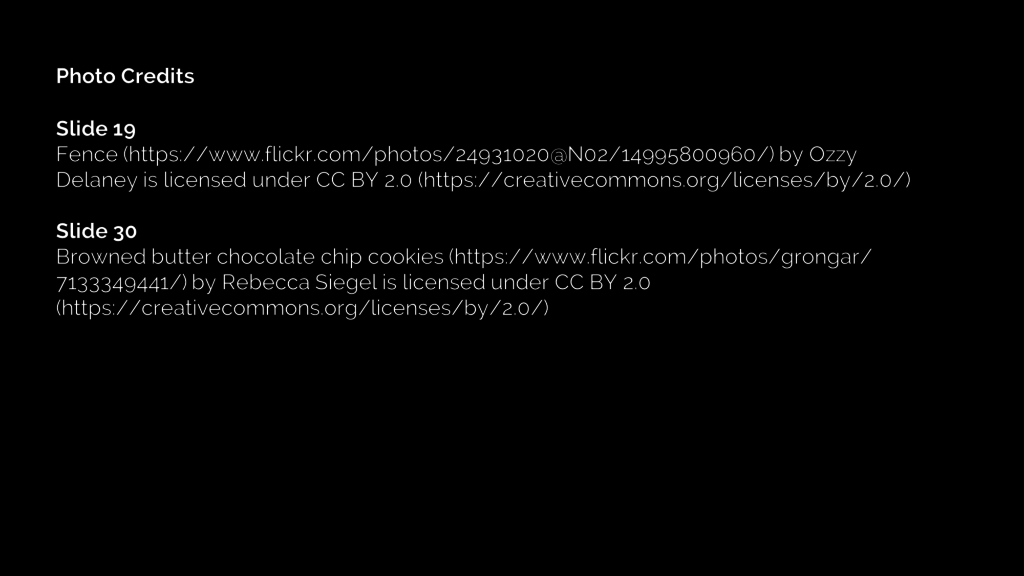

In a Video or Slide Presentation

Attribution can be placed in small print right on the slide or frame where the image appears. Because giving full attribution, including URLs, would take up a lot of space and could interfere with the enjoyment of the image, one solution is to place an abbreviated attribution where the image appears (giving the title, author, and license code), then add full credits on a slide or frame at the end.

Here’s what an on-slide attribution could look like, using a simple black rectangle at the bottom with a white-font text box on top of it:

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

And here is what the photo credits page might look like at the end of the presentation or video:

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Option 3: Buy Images

Although it’s not necessarily within most students’ budgets, they do have the option to actually purchase high-quality stock photography and illustrations. When making these purchases, students should read the licensing agreements carefully: In general, the more widely a user plans to distribute the product, the more the image will cost.

- On graphic design sites like Canva, where users can create their own designs with drawing tools and free images, there’s also the option to buy photos and illustrations to use in a single project for as little as $1. If the student wants to use the image in multiple projects, the fee for a single image can go as high as $100. Learn more about Canva licensing here.

- Other sites, like iStock, just sell the images without the graphic design tools. These images can be quite expensive depending on how they are going to be used and distributed. Learn more about iStock licenses here.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Don’t Make This Rookie Mistake!

When doing general searches for images, paid items will come up in the results. The way to identify a paid image is if it has a watermark: a translucent design that covers the image but doesn’t prevent you from seeing the picture behind it.

These watermarks are only removed after someone actually pays for the image, but it is possible to download a watermarked image, and people will sometimes do this without realizing that they are basically stealing the image AND broadcasting that fact to the world.

Teach your students not to do this.

Making a Good Effort

With all of this said, using images correctly can be an inexact science: Sometimes you can’t always contact a person for permission. Sometimes it’s nearly impossible to find the name of a photographer. The best rule of thumb is to make a good effort to give credit where it’s due and ask for permission as much as possible. If we can build these habits in our students from an early age, we will be helping to make the internet a more respectful and cooperative place.

Want a Ready-Made Lesson on Image Use?

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

I’ve pulled the concepts from this post into a ready-to-use lesson you can teach tomorrow. Using Images Correctly includes a beautifully designed PowerPoint (also available in Google Slides), two student handouts that summarize the key points, and a Team Challenge students can take to test their knowledge of appropriate image use. Come check it out!

All of the images in this post that have no attribution are licensed by CC0 or were created by the author.

Join my mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration—in quick, bite-sized packages—all geared toward making your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to my members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Come on in!!