Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Listen to my interview with Pernille Ripp (transcript):

Sponsored by Kiddom and mysimpleshow

This post contains Amazon Affiliate links. When you make a purchase through these links, Cult of Pedagogy gets a small percentage of the sale at no extra cost to you.

If I had to pick one thing that makes the biggest difference in the quality of any person’s education, the quality of their life, really, it would be reading. And I’m not really talking about basic literacy—not about the ability to read—I’m talking about reading for pleasure, to satisfy curiosities, to understand how people work and find solace in knowing we are not the only ones who think and feel the way we do.

That kind of reading.

But when I see what my kids do in school for “reading,” it doesn’t really look like reading. I ask them what books they are reading in school, and a lot of times they give me a blank stare. What they do in reading, they tell me, is mostly worksheets about reading. Or computer programs that ask them to read passages, not books, and answer multiple-choice questions.

Knowing this has bothered me a lot, and it led me to Donalyn Miller’s book, The Book Whisperer, and then to Kelly Gallagher’s book, Readicide. Both of these books show us that the reading programs and activities schools are using don’t work very well to raise students’ reading proficiency, especially if they take the place of real interactions with real books. And they certainly don’t do anything to turn our students into people who love to read.

The only thing that can do that is books. Reading actual books alongside other people reading actual books.

What baffles me is that this message still hasn’t reached so many schools. Schools are still shelling out thousands of dollars on expensive programs, putting pages and pages of passages and comprehension questions in front of our kids every day, sending them through the system without ever having them read a real book. Just excerpts. Just passages. Just reading-related “activities,” but little to no time with actual books.

So today I’m going to do what I can to get the message out there by having my friend Pernille Ripp on the podcast. Pernille is a seventh grade English language arts teacher in Wisconsin. She has been blogging for years, she speaks all over the country, and she has written several books about teaching.

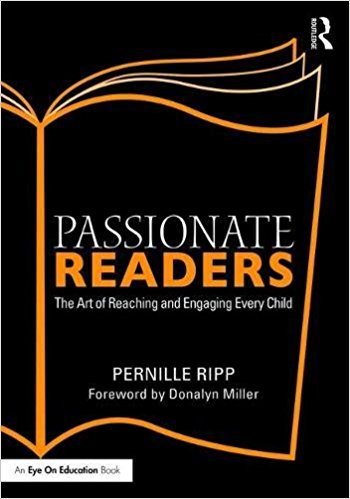

Clik here to view.

Pernille Ripp

Her most recent one is called Passionate Readers, where she writes about her own journey from teaching reading through programs and activities to teaching in a way that honors books and develops a love of reading in every child. It’s an awesome book. The best thing about it is how transparent Pernille is about her own doubts and struggles in this process.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

In our interview we talk about why she made the change, what her reading instruction looks like now, and how other teachers can change their own practices. The key takeaways are summarized below. You can read a full transcript of our conversation here.

What’s Wrong with the Way We Teach Reading Now?

In many classrooms that are feeling the pressure of high-stakes testing, instruction tends to emphasize what researcher Louise Rosenblatt called efferent reading, the kind of reading we do when looking for information, as opposed to aesthetic reading, which is done for enjoyment. Reading for information is a vital skill—without the ability to tackle challenging texts, locate evidence to support claims, summarize important ideas, and identify bias, students’ academic progress will be stunted.

Unfortunately, our push toward developing close reading skills has had collateral damage. In far too many schools, reading for pleasure has been treated as an afterthought, something we encourage but don’t really make time for. Instead of giving students time to read, we’re giving them activities, projects, computer programs, reading logs, and worksheets that detract from actual reading.

“We’re constantly reading for skill,” Ripp says. “We’re constantly asking kids to do something with their reading, and then wondering why they’re choosing to leave us and never picking up another book. They can’t wait to get out of school so that they don’t have to read.”

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

When she criticizes these practices, Ripp has no desire to teacher-bash. “I get it,” she says. “We are all kind of facing the pressure of our districts and our government and our testing and our parents and everybody’s focus on the data to show that these children can comprehend and compete with this global market economy that we’re a part of.”

“But unfortunately,” she explains, “what that has led to is just this further step away from what we know works within reading instruction.”

Even when we do have students read for enjoyment, we require evidence—reading logs, book reports, quizzes—to prove that the reading actually happened.

This was how Ripp taught for several years: “It was exhausting,” she says. “When we did book clubs, it was all about me, and I was reading five different books and coming up with all of the questions. All the kids had to do was show up, read aloud. There was no discussion about which book we were going to read or anything like that. It was just all teacher-centered, all the time, book reports just to prove they had read rather than doing meaningful work after they had finished the book.”

The Catalyst: What Caused the Change

Then one day a student said something that stopped Ripp in her tracks.

“I was doing the ‘reading is magical’ lesson that I think we all do at some point in the beginning of the year, and a kid in front of me whispered to his friends, ‘Reading sucks.’ And you know, I wanted to jump on him and be like, ‘Oh, you just haven’t found the right book,’ because how often have we said that?”

Instead, she asked him to tell her why.

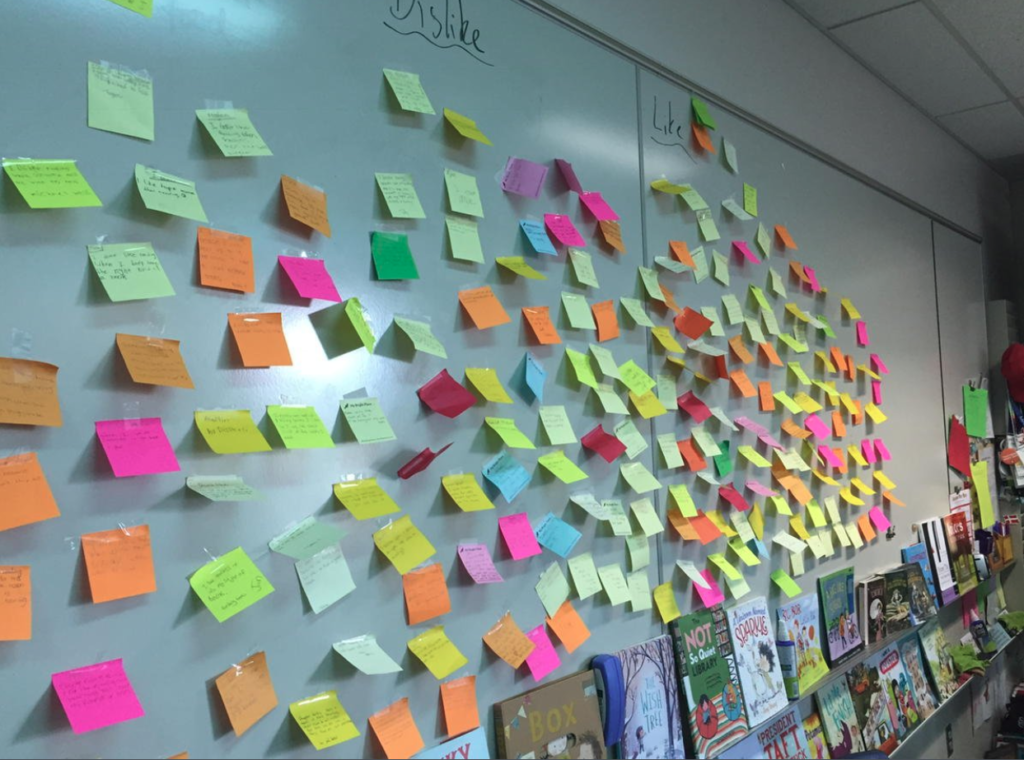

Clik here to view.

Every year, Ripp invites students to share their thoughts about what they like and dislike about reading on Post-its.

That’s when the floodgates opened: Invited for the first time to honestly share their thoughts about reading, students told Ripp that they didn’t like having to sit still. They wanted to be able to choose their own books, rather than being limited to a certain level. And more than anything, they hated the fact that every time they read something, they had to do some kind of activity related to the reading afterward.

Thus began Ripp’s journey toward what she calls a common sense approach to reading.

Returning to a Common Sense Approach

Once her eyes were opened, Ripp found herself drawn to the people she calls the “pioneers” of a type of reading instruction: Nancie Atwell, Donalyn Miller, Penny Kittle, Kelly Gallagher, Kylene Beers, Stephen Krashen, and so many others. She began to understand that scripted programs and reading-related activities—teacher-centered reading instruction—were not the way to help students become life-long readers. Over time, she shifted to a different approach.

When she talks about her current practices, she emphasizes over and over again that this is nothing new. “We have so many years of really great reading research out there, and yet it seems to be forgotten.”

Here are the most important components of Ripp’s reading instruction the way it looks today.

Time to Read

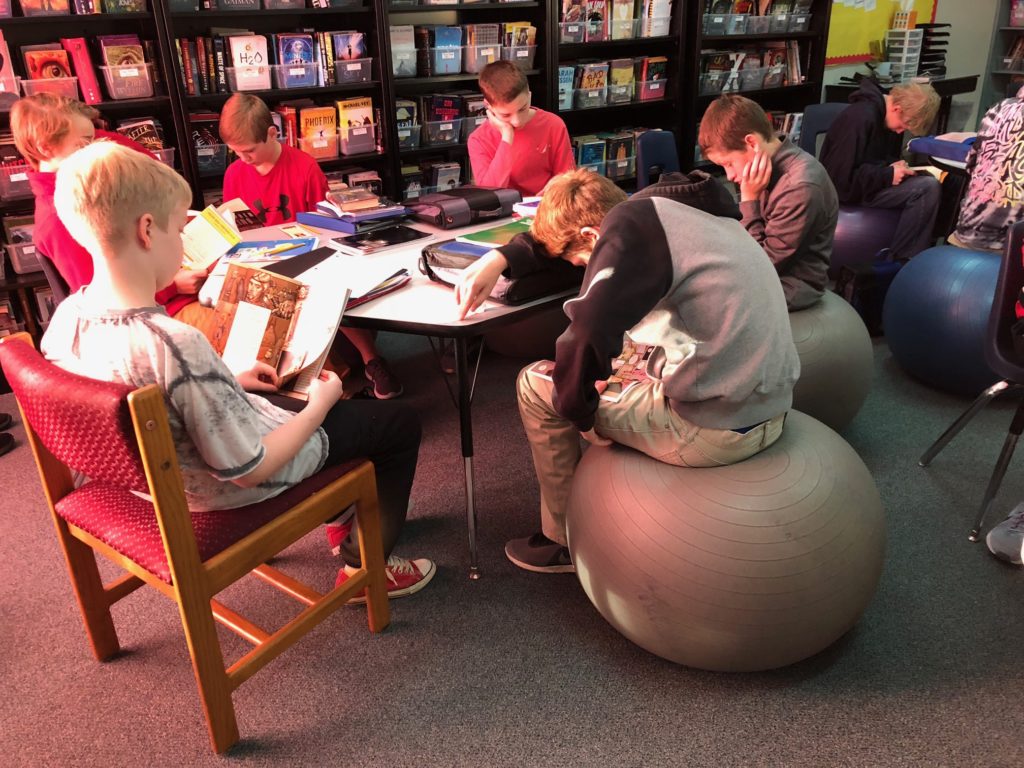

Ripp’s students are given ten minutes at the beginning of every class period for independent reading. “Every child, every day,” she says. Even though she only has 45 minute blocks with each seventh-grade class, she makes sure they get that time to read every day. “It is sacred time,” she says. When she taught at the elementary level, she was able to give students 30 minutes a day, but she no longer has that luxury.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

During that independent reading time, Ripp does check-ins with students. “I’m sitting down and I’m simply saying, ‘What are you working on as a reader?’ And it gives me that two-, three-minute connection with a child if they need to book shop, if they’re not doing well, to see what their reading identity is, where are they on their journey, and then I kind of pull all this information to think about what I still need to teach them (during the other part of class time).”

Students are not graded for this reading. “We can’t actually grade their independent reading, because that’s practice,” Ripp says. So there’s no other work associated with that time: no worksheets, no logs, no written reflections. “Nothing to do except to read. I want them to fall into the pages. I want them to reach flow. I want them to be silent and in this moment of their book.”

Ripp uses the remainder of the 45-minute period to have students work on the other things you’d expect to see in an English language arts classroom. “When they come back to me (after the ten minutes), we then do a mini lesson on reading or writing or whatever it is we’re doing, 10 to 15 minutes. And then they go and do something, and that’s where I assess them.” But those first ten minutes are always, always devoted to independent reading.

Choice

“Whenever I ask kids,” Ripp says, “‘What’s the one thing you wish all teachers of reading would do?’ (they say) ‘Choice.’ And yet, what do we do time and time again? We take away choice from kids, especially kids who might not be where we would hope they would be at this time. We end up with these limited choices for them, and then we wonder why they’re the ones that distance themselves from reading the most, because they never get to develop their reading identity. They never get to go through the selection process. They never get to just read and struggle with text and have meaningful conversations and sometimes yes, make the wrong choice.”

Students in Ripp’s class always have free choice of what they want to read during independent reading time. Through lots of conversations, students practice getting to know who they are as readers so they can make choices that work for them. “They’re constantly evaluating their book choices just either through conversation or self reflection or just their habits,” Ripp says.

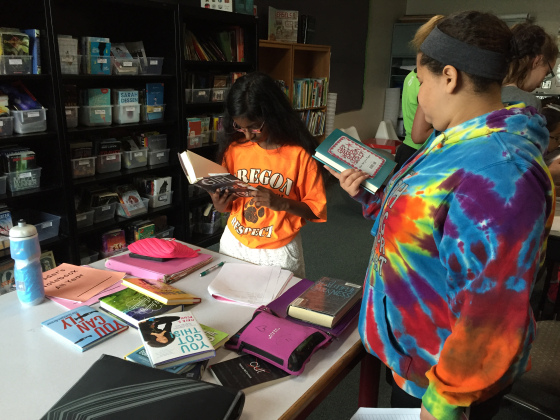

Clik here to view.

Students go “book shopping” for their next read.

If a student finds that a book just isn’t grabbing him, he is free to abandon it. “We should be celebrating when we abandon a book,” Ripp tells her students, “because we know ourselves enough as a reader to know that this will not provide us with a reading experience that will matter to us. And we need to start building up that stamina, so we need books that work for us at that time, and that’s really important for my students to remember, and to know and to recognize that what they need at this moment might be different than what they need a month from now.”

A Robust Classroom Library

Ripp’s classroom library houses several thousand books that students can check out at any time. You read that right: several thousand.

Why so many? “I need a book for every reader,” Ripp says, “and I teach kids that read from about a second grade level to a college level. I teach kids with lives that share no similarities at times and others whose lives are very much like my own. And so I need to make sure that every child has a chance of finding a book that will speak to them.”

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Where do they all come from? “(At the time I had) three kids at home, you know, on a teacher’s salary,” Ripp explains. “I can’t go out and spend thousands of dollars on books, and my school didn’t have a lot of extra money, but I would rather that a child can go up to this bookshelf and find a high-quality book pretty much any time they go there rather than have to dig through the junk and hope they find something. So it just became my mission that instead of buying things to make our classroom prettier or anything like that, I bought books. I used Scholastic, I went to library sales and parents donated books, and I was always really picky. It was big for me that the books were good, and then I just purchased books.”

Why not just have students use the school library? Ripp believes students need both. “Kids need to see the books staring at them at all times, and I think that has made the biggest difference for some of my kids who would go through the motions of going to the school library and they would even check some books out, but then when it came down to actually sitting down and read it, they didn’t feel that same need or urge to read it.” Her experience has proven the research that says students read more in classes that have good classroom libraries. “I had a seventh-grader come back to me my first year at the end of the year,” she says, “and he said, ‘You know what made the biggest difference? The books were always right there staring at me.'”

Ripp’s classroom library also includes an incredible assortment of picture books. Having lots of picture books in the classroom helped remove the “babyish” stigma many middle schoolers attached to them. “If you walk into our classroom, yes there’s all those books, the chapter books and all of that, but then all around us are picture books. And it’s just a vibe, right? You feel it when you walk in that this is a classroom where you can have fun and where you get to read and you can choose whatever you want. No one cares what you’re reading in our classroom, because you can pick up picture books at any time.” To start building your picture book collection, take a look at the tons and tons of recommendations for picture books Ripp offers on her website.

Culture and Community

A constant thread that runs through Passionate Readers is the sense that a classroom culture is constantly being built, that every day, Ripp communicates how incredibly important books are to a good life, and how, if we get to know ourselves as readers, and have lots of conversations about our reading, we’ll really get to experience the true magic of reading.

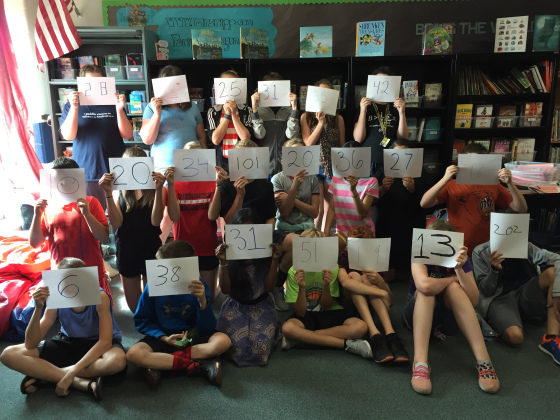

Clik here to view.

Every year, students are challenged to create their own reading goal based on their unique needs. Each student picks his or her own number of books to read by the end of the year.

The 7th Grade Book Challenge is one way she encourages students to build more reading time into their lives. This was adapted from the 40-Book Challenge introduced in Donalyn Miller’s Book Whisperer. Ripp participates in the challenge herself, just one of the ways she shares her own reading identity with her students.

Outside of things like the challenge, the culture is ultimately built on a day-to-day basis. “Teaching reading is not supposed to be quick and easy,” she says. “It’s supposed to be about human connection. It’s one conversation at a time.”

She admits that this new way of teaching is not perfect, and she’s constantly reflecting on how she can do better for her students. “We cannot go in there and expect every child to change, but we can go in there hoping that we can help,” she says. “I tell my students this: I’m not here to make you love reading. I’m here to make you hate it less. And if you already love it, then I’m here to protect it with all of my might.” Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Pernille’s book, Passionate Readers, goes into a lot more detail than I have room for here. It really walks teachers through how to implement a more reader-centered approach to teaching reading, complete with all the possible obstacles and pitfalls. I really encourage you to get a copy. To read more from Pernille Ripp, visit her fantastic blog at pernillesripp.com.

Join my mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration—in quick, bite-sized packages—all geared toward making your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Come on in!!