Listen to this post as a podcast:

Sponsored by Peergrade and Pear Deck

Suppose you know a lot about a certain topic. For the sake of argument, let’s say that topic is sushi.

One evening you’re on social media somewhere and an acquaintance posts this: “Have never tried sushi. Any advice?”

Oh my gosh! You totally have advice!

You start by sending your friend a link. Then you find another one. Then, well…there’s just so much great stuff out there! She should know about it. So you send her over to this Google Doc you made that contains more links:

I hate to break it to you, but your friend? She went to that first link you sent and read most of the article. It gave her some useful information—stuff she probably could have looked up on her own, but still. It helped. The second link she meant to get to, but she got called away from her computer and never got back to it. And your Google Doc? She took one look at it, got overwhelmed, and left.

And it’s a shame, because you have some really good stuff on that list. Especially the one in the right-hand column, second to last on the list. This one. It’s funny. And practical. It’s like a real person helping the reader find a way to add sushi to her life.

But your friend never read that one, because there was no way to sift it out from the others, no way to know what made it special, and like everyone else, your friend only has so many hours in the day.

You just dumped too much on her at once. You were being a dumper.

And it’s unfortunate, because you have vast experience with sushi. You really are the ideal person to hand-select a few resources that would perfectly meet her needs. Imagine if you had looked over your list and picked out a smaller number of items, then shared them in a way that would preview each one before she even opened it.

Something like this:

If you’d sent this to her, you would have been curating, not dumping.

I have written about curation before, but last time, I was talking about curation as a class assignment, something students do. Now I want to focus on you, the educator. Whether you’re a teacher, an administrator, a librarian, a researcher—whatever you do, chances are you have information to share with other people, and developing your curation skills—both in terms of how much you offer and how you deliver it—is going make that sharing a lot more effective.

So let’s take a look at how the brain responds to dumping, some school-related situations when good curation skills would come in handy, a set of curation guidelines to follow, and a short list of tech tools that can help you curate digitally.

Why Dumping is Bad for Brains

When we dump a lot of information on a person at once, we are working against their brain. Cognitive load theory suggests that the brain can only take in so much at once. When we’re presented with a whole bunch of information, our brains have to ignore some in order to process the rest. Eventually, if too much keeps coming at us, we reach the point of cognitive overload, where we get more than we can handle. At that point, a lot of people just shut down, and even simple information can’t get in.

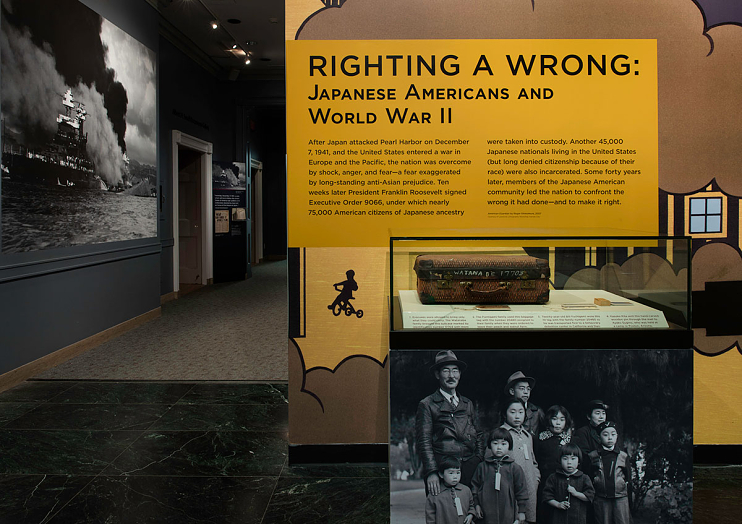

It’s a bit like this photo. Imagine being told to go learn something about history from the objects in this room.

“bric-a-brac” by Kevin Utting is licensed CC BY 2.0

No doubt, there are plenty of items in the room that have historical significance, but they’re all just dumped in there. Our brains learn by grouping lots of pieces of information into groups and patterns—cognitive scientists call these patterns schemas—and connecting it to knowledge we already have in long-term memory. Someone with considerable knowledge of the time periods represented in that room would be able to make some sense of it.

But the rest of us would do better off with the help of curators. That’s what a good museum does for us: It takes piles and piles of artifacts and selects only a few to represent an idea, a moment, an event, or a phenomenon. Then it carefully arranges those artifacts, starting with an introduction, often something written by the curators themselves to introduce the collection and provide us with meaningful context.

Then it introduces the artifacts in groups—again, adding its own editorial comments and explanations along the way, guiding us through the experience so that we aren’t forced to take too much in at once. We’re given time and space to savor each artifact one at a time.

Instead of being crowded into one big heap, items are grouped together under a common theme, so we see them as parts of a larger whole.

It’s not only museums that pay attention to this stuff. The tech industry is also very concerned with cognitive overload. In fact, there’s a whole field in tech called user experience design (UX for short). UX designers spend all of their time looking at how to improve the way users interact with websites and other digital products. They look at the smallest details, like the shape of the buttons we click, whether serif or sans-serif fonts get better responses, and where exactly to place a menu on a page. This article from Smashing Magazine does a deep dive into the topic, if you want to read more. Companies that invest in UX know that if they don’t bother with these details, you will eventually leave and go to another, better designed site. Even though educators don’t have the financial incentive to pay attention to this stuff, we should. Plenty of situations would give us better results if we did.

Sample Scenarios

Here are a few education-related scenarios where good curation could make a difference:

- Student-Directed Learning: As more classrooms move toward differentiated, flipped, blended, and student-directed learning models, we will need to do more gathering and sharing collections of resources for students to choose from, rather than picking one resource to deliver to everyone at one time. If our delivery is sloppy or our collections are thrown together kitchen-sink style, these models will be less successful. One of the most popular HyperDoc models includes an “explore” section, where a set of resources is provided and students choose which items to engage with in order to learn about the topic. Too many choices just dumped together will overwhelm most students. So offer choice, yes, but curate those choices carefully so students don’t waste a lot of time wading through all of their options.

- Classroom or school libraries: If students aren’t checking out books very often, you may be able to improve things with more curation. This may come in the form of aggressively weeding out books that students have no interest in, a process teacher Pernille Ripp described as an essential step toward building a thriving classroom library. It might also include creating special displays of books grouped around a common theme, or posting student recommendations on specific books like they do with staff recommendations in bookstores.

“Staff Favourites – University of Washington bookstore” by brewbooks is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

- Communication with Parents: When we send newsletters, flyers, and emails home to parents, we obviously want them to be read. But as a mother of three, I can tell you that an awful lot of skimming is happening. With that in mind, we will have much greater success if we apply some basic curation and design principles to those items. I wrote about this in a guest post for Corkboard Connections a few years ago: Why No One Reads Your Classroom Newsletter.

- School or Teacher Websites: It seems that one company designed the basic template for all school and district websites around maybe 2004, and since then, far too many schools have never strayed from that. I’m not going to point fingers at any one school, but I think you know what I mean: The menu has hundreds of items, the page is broken up into dozens of little squares of information, and everything is in 12-point font. No white space. They are functional, yes, but cluttered. By contrast, take a look at the websites of The Dalton School, in New York City, Vail Mountain School in Vail, Colorado, or the Gibraltar School District in Woodhaven, Michigan. These sites make me want to click around, learn more. They make me excited about the learning that is happening in these schools. And it all comes down to the design, the thoughtful way the content is organized with the user experience in mind.

- Sharing Research: Maybe you’re trying to convince your team to try a new method. Maybe you’re an administrator who wants your staff to learn more about a certain learning theory. Maybe you’re delivering PD to a group of teachers. Or maybe you are the one doing the research and you want to get it out to the world. In any of these situations, taking the time to narrow your focus to just a few items, then share them in a way that’s appealing will make it more likely that people will actually consume the stuff you’re sharing. For in-person delivery, getting better at slide design and presentation can help a lot; for that, I recommend Garr Reynolds’ book, Presentation Zen. For online sharing, check out The Learning Scientists and RetrievalPractice.org—both are excellent examples of taking complex research and making it consumable for a wider audience.

Curation Guidelines

In any of the above scenarios, keep the following guidelines in mind when deciding what to share and how to share it.

1. Keep the Best, Lose the Rest

Less is almost always more, so once you get to the point where you’re sharing multiple resources on the same topic, you should be able to get rid of some and keep only the very best. This is easier said than done, because you want to be helpful and every additional item probably does add something unique to the mix. Just keep reminding yourself that the goal is to have the person actually consume the thing you’re sharing, and too much will send them running for the hills, so keep paring it down until it’s a nice, manageable size.

2. Chunk It

If you are sharing more than just a few resources, break the collection into smaller sub-sets. Give each section some kind of title to help users find what they are interested in more quickly.

3. Add Your Own Introductions

Just like museum curators place an explanatory paragraph near most artifacts, you can do the same with your resources. Give your audience some context to help them know what the resource is and what they will learn from it. Another way to do this is to offer a brief preview or excerpt from the article itself.

4. Use Images as Anchors

Although this can take extra time, adding an image before each item, like I’ve done below for the list of tools, can help readers visually distinguish one item from another. It will also help them find items more quickly later on.

5. Polish your Hyperlinks

When your resource sharing includes a link to something, you can provide that link in one of two ways. Giving the person the raw “http” link will certainly work, but these links usually look cluttered and complicated. What’s more appealing to the human eye is text that tells us something about the thing they’re clicking over to. You can accomplish this by changing the link text.

So instead of saying here, watch this: https://www.ted.com/talks/susan_david_the_gift_and_power_of_emotional_courage

You could say here, watch this TED Talk about Emotional Courage.

Every program does this a little bit differently, but once you’ve learned how to do it in one place, you should be able to figure it out in other places. To get you started, here’s a quick tutorial for how to insert a link in a Google Doc.

6. Always, Always Build in White Space

I can’t emphasize this one enough. Creating space around your resources is essential for a good user experience. So whether you’re sending an email, creating a newsletter, or designing a bulletin board, avoid cramming items together. Instead, cut back on the number of items and give your audience’s eyes some rest.

Curation Tools

For times when you’re curating digitally, these tools can help:

elink

elink.io

This is probably the simplest of all: Just insert a link and the tool lets you add your own introduction paragraph and image. This is the one I used for the sushi example at the beginning of this post.

Pinterest

pinterest.com

Save links to resources on themed boards, then share those boards with others.

LiveBinders

livebinders.com

A LiveBinder is like an online notebook, where you can organize collected items under individual tabs. In a single LiveBinder, you can gather links to websites, videos, uploaded documents, and personal notes you type in yourself, making this an excellent tool for larger, more complex collections.

Sutori

sutori.com

Collections on this platform are organized as vertical timelines. This is an especially nice option if you want your audience to experience your collection in a specific order, almost in the same way that a museum creates a “path” for visitors.

Padlet

padlet.com

This virtual corkboard offers a nice space for posting notes, images, and links to online articles and videos. Because it has good features for collaboration, this is a nice option for curating a collection with other people.

HyperDocs

A HyperDoc is not a specific website or app: You make these yourself out of a Google Doc. The HyperDoc framework would be perfect for building and sharing collections of resources. Learn more about HyperDocs here.

Why Bother?

So what’s the point of all this? We’re not running a museum. We’re not designers. Our job isn’t necessarily to entertain and enthrall our students with graphic design and finely tuned UX. So why bother?

Apart from the fact that it just makes things work better, developing our curation skills is just another way to elevate our craft. We have machines to provide information, to dump it all in a pile in front of us. What really smart, intuitive humans can do for each other—as teachers, as colleagues, as administrators—is curate. If we aspire to call ourselves master teachers, we also should be clear on what that actually means. The essence of our work is taking vast swaths of information and helping our students make sense of it. As college instructor Norman Eng says, “Think of yourself less as a teacher and more as a designer of meaningful experiences.” We’re going to share the information anyway; we might as well do it with style.

Join my mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration—in quick, bite-sized packages—all geared toward making your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 other teachers have already joined—come on in!