Listen to my interview with Victor Small (transcript):

Sponsored by Pear Deck and Peergrade

This post contains Amazon Affiliate links. When you make a purchase through these links, Cult of Pedagogy gets a small percentage of the sale at no extra cost to you.

A student threw a chair at a teacher.

That’s the story I heard. It was a story meant to illustrate how bad a particular group of kids was, and now I can’t even remember who the teacher was or where the school was located, or even the gender of the teacher or the student. In fact, I’m pretty sure I’ve heard two or three different stories about students throwing things at teachers, each one told with the intent of showing just how bad those kids were.

But every time I’ve heard a story like that, my first thought has always been, Holy crap. What kind of a relationship did that teacher have with those students? What was going on in the minutes, days, and weeks leading up to that chair being thrown?

And I know how that sounds. It sounds like I’m blaming the teacher. Or that I don’t think a student should be held responsible for doing something as awful as throwing a piece of furniture at another human being.

I don’t think that. But here’s what I think probably happened in all of those schools: The student was removed from class and promptly suspended, maybe even expelled. And if and when that student returned to school, nothing much was done to repair that student’s relationship with the teacher. Or to really address the other issues that may have been going on leading up to that chair being thrown. And if that kind of work isn’t done, if we focus only on making our punishments stricter, then things like chair throwing will keep happening. And nobody wants that.

Getting students to behave in a way that is conducive to learning is a perennial challenge for teachers. On this site I have dealt with the topic a number of times. And every piece of advice—the tips and hacks and bits of wisdom—they are all useful.

But one approach to addressing problematic behavior—restorative justice—really stands on its own, because it focuses on building relationships and repairing harm, rather than simply punishing students for misbehavior.

I have wanted to share more about restorative justice on my site for years, but every time I started, I found that the topic was just too big, too complex to handle all at once. Usually, I try to share things that teachers can understand and apply right away, and the concept of restorative justice just wasn’t letting me package and deliver it in a tidy little bundle.

So rather than try to do that, I’m going to just start with an overview. This will not be a comprehensive study of restorative practices, but an introduction designed for teachers who are just starting to get interested in this approach.

Victor Small, Jr.

Helping me do that is Victor Small, Jr., a middle school administrator in Oakland, California. He has been using restorative practices for several years and supports other teachers through a Twitter chat—using the hashtag #RJLeagueChat—and a Voxer group called the Restorative Justice League, where educators talk about the challenges they’re facing in implementing restorative practices and help each other work through tough situations.

In our interview, Small walks me through some of the basics of restorative justice—called RJ by many of its practitioners—and talks about how teachers can get started. You can listen to the interview in the player above, read a full transcript, or review the key takeaways here.

What is Restorative Justice?

The philosophy of restorative justice has its roots in the criminal justice system. When a crime is committed in a modern society, the typical response is to punish the offender, and that’s about it. But societies all over the world have started to recognize that this approach doesn’t repair the harm that was done; it also does nothing to address underlying problems that may have led to the offense in the first place. So they are starting to replace—or at least supplement—the standard approach with restorative justice practices, which focus on repairing harm for all parties involved. This process may include some form of punishment for the offender, but the lens is much wider than that.

“Say you stole a car,” Small says. “Instead of you necessarily doing jail time, really what you would have to first do is make sure that you restore the situation to the person who you actually harmed, which would be the person whose car you stole, right? So you would have to restore that in some way. Either you’d have to get them their car back or get them a new car and apologize or something like that. Basically, the debt that you owe to society is to that person that you harmed.”

This shift toward restorative justice has led to reduced recidivism (repeat offenses), greater satisfaction with the outcomes from all stakeholders, and reduced post-traumatic stress caused by the crime. (These results are summarized in this overview from the University of Wisconsin.)

Encouraged by these successes, educators in some schools have started using restorative practices to address disruptive or harmful behavior. With this shift, schools hope to see improved behavior and to reverse a disturbing trend: The zero-tolerance discipline policies of the past few decades have dramatically increased suspension rates in many districts, which can in turn lower graduation rates and ultimately push more students into the juvenile justice system. And again, those suspensions do nothing to repair harm.

Common Restorative Practices

The thing about restorative justice is that unlike a typical discipline program, it is not a cut-and-dried system with prescribed steps to follow in every situation. If done correctly, schools that shift to restorative justice will approach it holistically, looking at preventing wrongdoing as much as—if not more than—how to address it when it occurs.

“What we’re essentially teaching students is your behavior affects people,” Small explains, “and so in order to pay it forward or to deal with the consequences of that, you’re going to have to figure out how to make things right. When we talk about restorative justice practices, we’re talking about the things you’re doing to ensure that students are recognizing when they’re doing something wrong and finding a way to make it right.”

Although restorative justice models vary somewhat from school to school, Small says schools that are doing it right have the following practices at their core.

Building Relationships

Schools that get interested in restorative justice may be tempted to jump right to the alternative punishments, but a true RJ program puts heavy emphasis on relationships. These relationships go in all directions: teacher to student, student to student, teacher to teacher, and between the school and the larger community.

These bonds are not forged overnight. Daily conversations, team-building exercises, telling our own stories and making time and space for students to tell theirs helps build relationships over time. “You’ve got to give them time to grow with one another,” Small says.

And if you do, it pays off. “If you’ve got everybody in the school liking and getting along with one another, well when they do something wrong, it’s a lot easier for that kid to apologize. The reason I’m really a very big proponent of RJ is if you’re doing it right, you’re going to prevent a whole lot of issues from occurring.”

A Mindset Shift

To be effective with restorative justice, teachers need to adopt a restorative mindset, a way of looking at wrongdoing and punishment through a different lens.

“Everything that a kid does shouldn’t have to have a consequence,” Small says. “I mean if a kid gets angry and says something to another kid, and that kid gets mad, do they need detention for that, or do they need to just fix the problem and not be mad at each other? Probably just fix the problem, not be mad at each other, and go on about their lives. If they didn’t do anything wrong to the class or the community and they just did something messed-up to another student, they can handle that between the two students. You could facilitate that. It teaches them, hey, you have to be accountable for your actions, because your actions do have impact on other students, without having them sit in detention, right?”

Circles

Pulling groups of people together into circles for conversation is one of the most recognizable features of schools that have adopted restorative practices. These circles can take many forms: mediation circles when a problem needs to be addressed, healing circles when group members are hurting or grieving, or circles that form just for dialogue and storytelling. When circles are a regular part of the school culture, they give students a vehicle for communicating when problems arise, rather than handling them in less constructive ways.

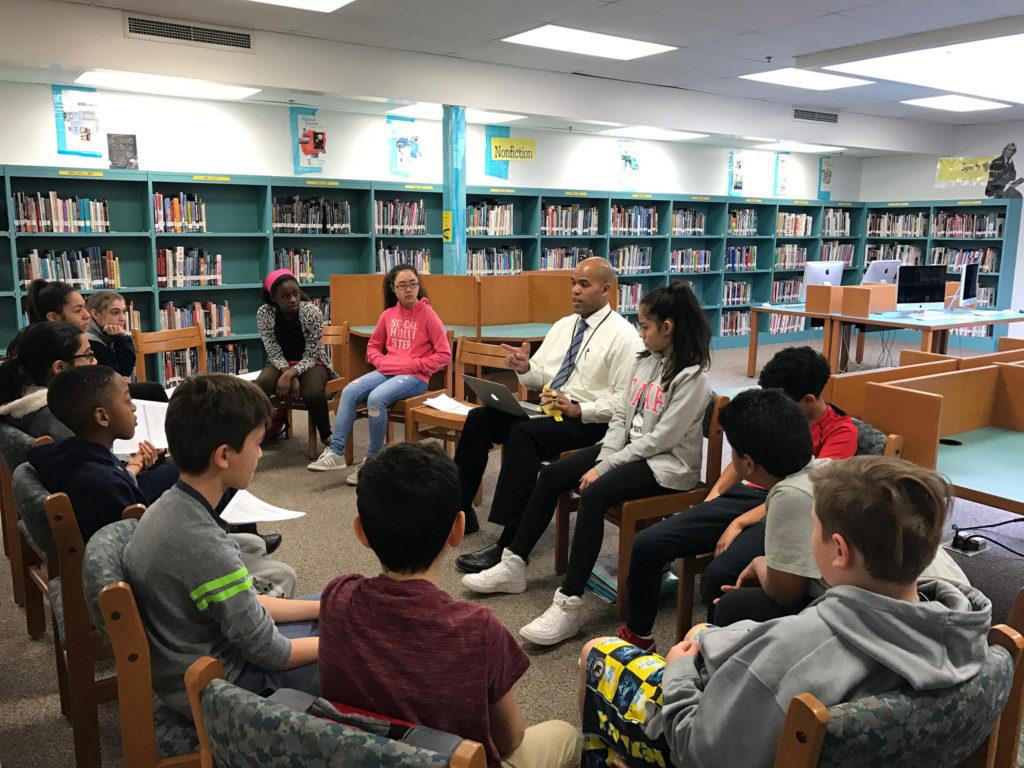

Teacher Hakim Jones leads a circle at Murray Hill Middle School in North Laurel, Maryland (photo by Gwyneth Jones, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Where to Start

Small offers this advice for educators who want to get started with restorative justice:

Read about RJ

A lot of excellent books have been written about restorative practices. To make sure you and your colleagues are working from a solid foundation, read up on the history and philosophy before attempting to implement an RJ program. I have listed a few good starter books at the end of this post, and a lot more can be found online that detail specific practices.

Identify Your Biases and Triggers

A big part of addressing student misbehavior and building strong relationships with students is uncovering our own built-in biases. And the first step toward doing that is getting comfortable with the idea that we all have them.

“It’s really painful for us to consider this,” Small says, “but if we walk into our classrooms and we really try to believe that an approach to colorblindness is one that’s effective, we’re really shortchanging our kids’ lives, because if we’re just constantly telling them, ‘Hey, I don’t see color,’ when they leave your classroom, someone’s going to see their color. And someone’s going to act possibly on the fact that they see their color, so we’re setting them up for failure if we don’t do our own investigation of, ‘Do I have any biases against any particular type of culture, any particular type of culture activity, any of my students? Do I have any things that trigger certain behavior or fears or anger that they do that they do naturally? Taking a step back and wondering, is it me or is it them?'”

Build Culture and Community

If you have a school culture where students feel known, where they feel at home, behavior on the whole will be better and efforts to address wrongdoing will be more productive. Getting to that point will happen if you approach culture-building from a lot of different angles.

“Work on finding ways to include kids in what’s going on,” Small says, “like allowing more student voice, allowing more student opportunities for them to display their culture, act on their culture, be a part of their culture.”

Having caring adults in the building who look like the student body is also more important than many people realize. “You need to give (students) opportunities to learn about people that look like them, that are from their culture, that represent them. If 99 percent of your staff is white and 99 percent of your student body is black and Latino, you’re going to need to figure out a way to get more black and Latino staff members in your school.” (This conversation with former teacher of the year Nate Bowling dives more deeply into this topic.)

Finally, schools can work to make the school more integrated into the larger community. “If you can find ways to learn about the neighborhoods, the communities and find ways to bring people from the community and in the neighborhoods into your school, you’re creating a school culture that the students can feel more at home in.” And when students feel at home, when they know each other, there’s less of a need to address misbehavior.

“They just get along better, so they fight less,” Small says of his students. “There’s less reason for them to fight, because everyone knows everyone else.”

Okay, but what about the discipline?

Having finished this overview, I realize I never quite got to the question of How does restorative justice actually deal with the misbehavior?

The answer to this is complicated, because it’s not as simple as detention-suspension-expulsion. There are conferences and circles, a lot of discussion about the harm that was done and how it can be repaired. Individual decisions are made on an individual basis. There’s more to it than I can cover in one post, but I plan to do more posts later to dig more deeply into the details. I really do believe that restorative justice is the direction we need to be heading to create safer, healthier school communities.

I hope you’ll take a step in that direction.

To Learn More

These books offer a great starting point for learning more about restorative practices:

Better than Carrots or Sticks:

Restorative Practices for Positive Classroom Management

Dominique Smith, Douglas Fisher, Nancy Frey

The Little Book of Restorative Justice

Howard Zehr

The Little Book of Restorative Discipline for Schools:

Teaching Responsibility; Creating Caring Climates

Lorraine Stutzman Amstutz, Judy H. Mullet

You can find Victor Small, Jr., on Twitter at @MrSmall215, and join him every Sunday night at 8pm EST for the #RJLeagueChat.

Join my mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration—in quick, bite-sized packages—all geared toward making your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 other teachers have already joined—come on in.