Listen to this post as a podcast:

Sponsored by Screencast-O-Matic and Microsoft Inclusive Classroom

My daughter was recently given an assignment to create a model of a volcano. It was a group project, meant to be done entirely at home, and the main criteria was that it had to look like a volcano, with extra points if it could actually erupt.

And so it began: My daughter and I planned when her two friends would come over to work on it. I texted their moms and we set a date. We also figured out what supplies she’d need from the craft store and when I would drive her there to get it all. We ended up spending about $40 on modeling clay, spray paint, fake palm trees, and tiny dinosaurs. And that’s after I said no to about $40 worth of other stuff she wanted to get.

The three girls met at our house one afternoon. One of the other parents brought over the materials they used to make the volcano erupt. I insisted that they do the project in the dining room, where we could make sure they stayed on task, instead of my daughter’s bedroom, where I knew they wouldn’t. My husband helped them hunt through the basement for an old lampshade to give the model some height, helped them figure out how to make the clay stick to the lampshade, then did a few trial runs of the “eruption” with them, so they knew it would work in class. A few days later, I drove my daughter to school and helped her walk the model safely into class.

So much had to happen to get this assignment done, and very little of that was actually done by the three students whose names went on the project. I’m not saying my daughter and her friends didn’t build the volcano, but they got a lot of support along the way, and if any of that support had been missing—time, transportation, money, space, suggestions, supervision—the project would have been less successful.

When I ask my daughter about the other student projects that were turned in that day, she confirms my suspicions that they ranged in quality: Some, she says, were “huge and detailed,” while others consisted of little more than a painted water bottle.

Though I never confirmed it, I suspect that each of those projects got vastly different grades.

What Are We Measuring?

Although a movement is growing to eliminate grades, they are still a reality for most of us, and they impact everything from college admissions to whether students get to go on certain field trips. So it’s important that we do whatever we can to make sure they measure what matters.

And in too many cases, that’s not happening. Take the volcano project: The grade students received on that ultimately reflected the resources each group happened to have at home—not what they learned or even the effort each student personally put into the task. Those with the “huge and detailed” ones probably got the best grades, and those with the painted water bottles probably got the lowest.

Or consider these other scenarios:

- The student whose essay gets a D, because even though he organized it pretty well, made some strong, well-supported arguments, and used rich vocabulary, his teacher’s rubric allotted 40 percent of the grade to neatness and correctness, and he had a lot of mistakes. The teacher lets him revise for a higher score, but only gives half credit for the points earned the second time around.

- The student who raises his grade by earning extra credit for donating tissues and hand sanitizer to the class.

- The student who gets a C on an assignment that requires her to compose an original song to explain a constitutional amendment. Despite her solid understanding of the constitution, she doesn’t happen to have a knack for writing lyrics and music.

- The student whose project is turned in a day late and gets only half credit according to her teacher’s “no excuses” late policy.

In all of these cases, the grade is not an accurate representation of what a student has learned. This is a problem of design: When constructing assignments, assessments, and grading policies, every teacher makes dozens of small decisions that determine how much a grade reflects a student’s academic work and how much it reflects a mishmash of other factors. Those quantities are different for every teacher and every assignment. Despite that, we tend to treat grades as if they mean the same thing all the time.

Some Questions to Ask While Planning

So what’s to be done about this? If you or your colleagues aren’t ready to completely overhaul your grading system (again, see how others are doing that here), or you haven’t moved to standards-based grading, you can still improve the integrity of traditional grades by considering some important questions while planning for instruction.

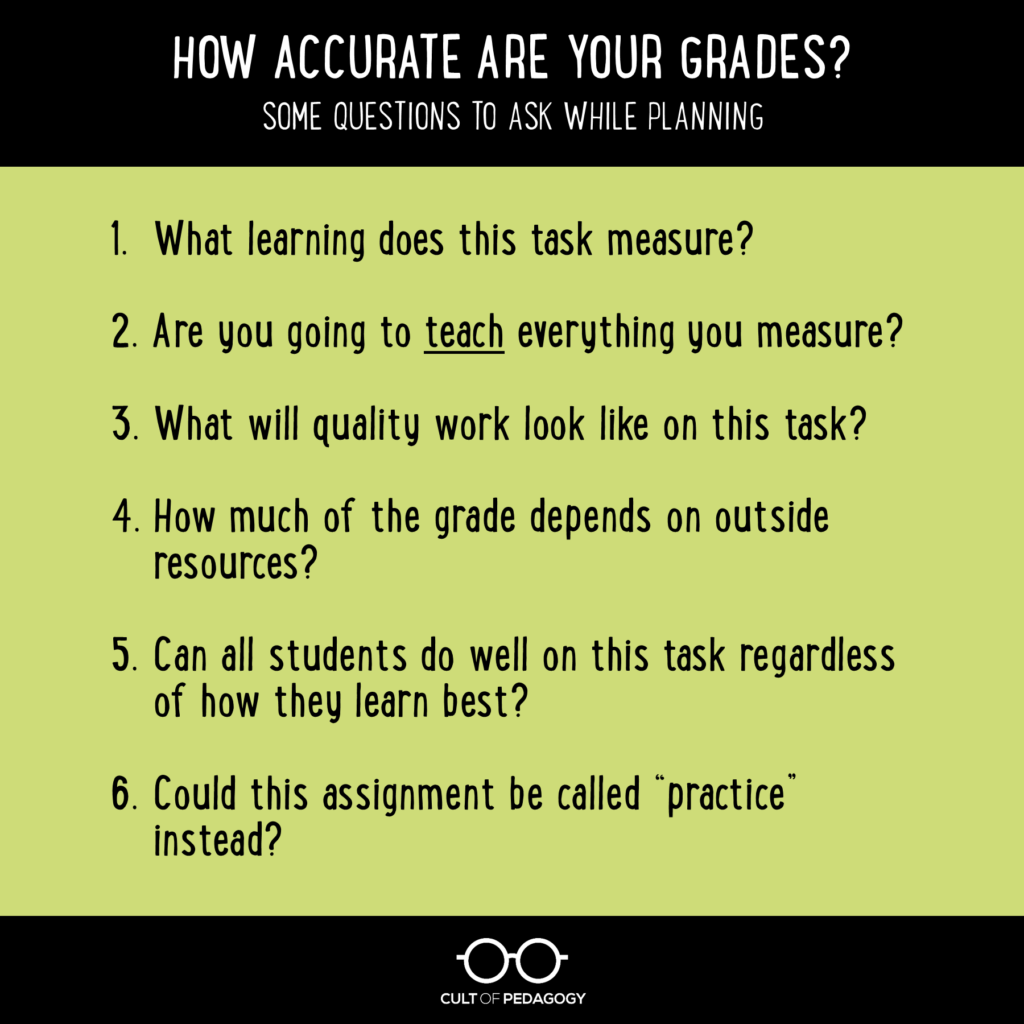

1. What learning does this task measure?

The grade on an assignment should match the learning students are supposed to be doing in your class. This sounds simple, but it amazes me how often I see assignments that seem to have no real connection to what the curriculum says students are learning.

If your standards require students to “be able to explain how geography impacts culture,” then assignments should ask them to do some variation of that: explain how geography impacts culture. If, instead, they are making a relief map that shows geographic features, and their grade is based largely on how accurately they represent those features, then they are being graded on map-making skills, not on the standard.

This is especially problematic when qualities like “creativity” are part of your criteria. For one thing, this term means completely different things to different people, so students will have to guess how to perform well on this metric. More importantly, grading for “creativity” on an assignment that is supposed to measure something else will distort the results, making it much harder to tell who actually mastered the skill.

2. Are you going to teach everything you will measure?

We often assign points for skills and qualities that students happen to bring with them, but are never taught in our class.

Suppose you assign a group project, and part of each student’s grade will be based on how well he or she worked with the group. Collaborative skills are important, absolutely, but if you’re grading for them, shouldn’t you also be teaching them?

Similarly, if you’re going to ask students to do an essay-type question to demonstrate their learning, and part of their grade will be based on how effectively they write, then ideally, some of your teaching prior to that assessment should give students practice in the kinds of writing skills you want to see on that task.

If our lessons don’t prepare students to do well on graded assignments and assessments, then those grades aren’t a fair measurement of learning in our class.

3. What will quality work look like on this task?

When creating assignments, we often have a general idea of what a good end-product will look like, but we don’t always know for sure until the work gets turned in. At that point, it’s too late for students to rise to our expectations, and if we haven’t clearly defined them ahead of time, it’s easy for personal bias to cloud our judgment.

We’ll get better work from students and judge it more fairly if we identify and communicate the criteria for success ahead of time. Many teachers accomplish this with a rubric given to students before they start. These come in different formats: A growing number of teachers are finding that students appreciate the single-point rubric for its clarity and ease of use.

I would also strongly recommend you do the assignment yourself as if you were a student—a process we call dogfooding. This will help you get much clearer on how you define excellence for this assignment.

4. How much of the grade depends on outside resources?

If an assignment is going to be completed partly or entirely at home, take a good look at how much the available resources outside of school could influence the grade. Things like transportation, money for supplies, access to technology, or help from an adult can all contribute to an end product that looks impressive, but may not directly reflect that student’s academic skill or effort.

If your assignment is designed so that the focus stays on content and skills, and if you set things up so that the majority of the work happens in class, the assignments you get back should be a more accurate representation of what each student can do.

5. Can all students do well on this task, regardless of how they learn best?

If an assignment is delivered with only one type of learner in mind—with instructions only given verbally, for example—some students will be behind before they even start. Ideally, every task will be designed in a way that all students can access.

Universal Design for Learning is a framework that can help teachers design materials so that all learners have equal access to them. To learn more, watch this overview video or explore the UDL Guidelines developed by CAST. As you work to make your assignments more universally accessible, take a look at some of the great accessibility tools Microsoft offers teachers for free.

Similarly, if the task favors students who happen to have a specific type of artistic skill—the way the constitutional song assignment did for students with musical talent—others who might have preferred to demonstrate their learning through an essay, a poster, or a video are less likely to shine.

Instead of limiting student products to a single, narrow option, consider whether you can give them choices in how they demonstrate learning. If the volcano project had been designed for students to create a model for how a real volcano works, that model could have been done with a paper diagram, in a video, with a student-produced skit, or with a physical model. Not only would this give students an opportunity to put their unique gifts to use, it would also provide options that cost a lot less money to bring to fruition.

6. Could this assignment be called “practice” instead?

Too often, teachers give grades to all classroom activity; they are convinced that kids won’t do something unless it’s going to get a grade. And that means tasks that are really meant to give students practice in a skill or early exposure to content are ultimately included in final grade calculations.

They shouldn’t. Instead of making everything graded, have students do some class work as practice, in preparation for a task that will be graded. So if students have to take a test on long division, require them to do enough self-graded practice pages until they get 80 percent or better. These problems won’t be part of their final grade calculation, which also means you don’t have to grade them, but students can’t take the test until they can demonstrate proficiency on the practice, and their grade on the test will count. This way, their grade will reflect their mastery of long division without penalizing them for how long it took to master the skill.

Other Factors to Consider

Late Work

Some policies on late work can have a significant impact on student grades, so that a student who turns work in late can have very low grades, even if they have mastered the content. In classes where late work is penalized, a grade is a reflection of the student’s time management, or of stress, or perfectionism, or dozens of other possible factors. What it isn’t is a reflection of learning.

Despite this, many teachers feel that taking points is their only option for responding to late work. This piece by Starr Sackstein explores this dilemma and considers some ways teachers can address the problem without docking points. Spoiler alert: It’s not a one-size-fits-all solution, because students turn work in late for a variety of reasons. “At the root of every challenge we face with students of all ages is a story,” she writes. “Our job as teachers to figure out what the story is. Some students will be an open book and others we will need to be detectives to figure stuff out. Don’t give up on the kids. Giving a zero is giving up and almost expecting them to do the same.”

Extra Credit

Giving points for anything that doesn’t directly reflect learning can have an incredibly distorting effect on grades. In some cases, it elevates grades, giving the impression of mastery without the actual mastery. In other cases, it masks problems: If a student misses a few test items, but erases them with bonus points, that student could fly under the teacher’s radar and miss opportunities for reteaching.

Students who are doing so well on the regular class work that they finish early don’t need extra credit, they need differentiated assignments and more challenge. Students who do poorly on assignments don’t need extra credit to make up the missing points; they need opportunities to re-do and improve on the work.

This piece by Joy Kirr does an excellent job of showing how a variety of typical extra credit assignments are rife with all kinds of problems.

Grade Averaging

If you calculate your grades by simply averaging them—dividing the points earned by the total possible points—your final course grade could be doing a poor job of representing what your students actually learned in your class. In this piece on the pitfalls of grade averaging, Rick Wormelli uses specific examples to illustrate this problem.

Having graded this way myself, I always liked the simplicity and convenience of grade averaging, so I know that the thought of trying some other system will likely be daunting. But if it means our grades will have more integrity, it’s worth it.

One alternative to consider is something called a decaying average, which puts more weight on assignments done later in a learning cycle. In theory, this recognizes that skills should improve over time. Although this approach seems to work better in skill-based classes, it shows us one way to rethink the way we calculate grades so they are better aligned with who our students are as learners.

Grades are inherently imperfect. To truly assess our students’ learning, we need to get to know them, observe them, and study a wide sampling of their work over time. When we reduce all that to a single measurement for the sake of efficiency, we lose that bigger picture. But as long as grades remain a reality in our system, let’s be thoughtful and deliberate when we calculate them.

Join my mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.