Listen to my interview with Marisa Thompson (transcript):

Sponsored by Peergrade and 3Doodler

So much of the learning we do comes from texts: articles, textbooks, novels, and all kinds of online publications. Sometimes, those texts come in less traditional forms; in fact, our use of the word “text” has broadened over time to include things like films, images, and even diagrams. Regardless of what form they come in, texts make up the bulk of how our students experience learning.

But too often, when we assign texts to students, we find that they don’t experience them with much depth. One reason for that may be that we don’t set them up to do that. In many text-based classes (English, history, science), the learning cycle often consists of (1) consuming a section of the text, (2) answering teacher-created questions about the text, (3) taking a test after several sections have been completed.

For years, high school English teacher Marisa Thompson followed this same programming, and got typical results: Some students did the required work, but never seemed particularly invested in the books themselves. Others completed the questions unevenly, sometimes not answering them all, other times copying work from their peers. And when students didn’t do the work, they got calls home and office referrals.

As this pattern repeated itself year after year, Thompson became more frustrated: The texts themselves were wonderful, but students weren’t experiencing them the way they were meant to be experienced. Instead, they had shallow interactions with them, doing whatever surface work had to be done to get a grade.

Marisa Thompson

Finally, she started experimenting with a different approach, and the way she teaches texts now is completely different from the way she used to. Her current approach, which she calls TQE, is similar to Socratic Seminar, where students lead a discussion on a given text, but with a few twists. Since implementing this new approach, Thompson has seen her students reading much more than they used to, and with much more depth than ever before. They are having college-level conversations about books in class, and for the first time, they seem excited about the books they’re reading.

On top of that, Thompson’s prepping and grading work for these class sessions is down to almost nothing.

What I love about this method, and why I’m sharing it here, is that I think it could be applied in a lot of different areas, not just with the study of novels. In any class where students need to read a text in order to learn, something along these lines could be implemented, and I think you’ll find that the learning in your classroom gets much richer as a result. So as you read about TQE, think about how you might be able to apply it in your content area.

The Problem

As an English teacher, Thompson found that her students were experiencing books in a very shallow, grade-focused way.

“(I would) send students home, maybe get them started on Chapter 1, and then, Hey guys, go home and read Chapter 2. Come on back and we’ll talk about it, and here’s your list of questions; you’re going to have a reading quiz. I realized I wasn’t really assessing their reading with homework and quizzes. I was assessing whether or not they did their homework questions.”

This method not only diminished the value of the books students were reading, it also led to other problems. “It made reading seem like a hassle,” Thomspon says. “I started getting a bunch of cheating. One year I had 10 kids copy off each other. It turned this amazing story—this beautiful novel that everybody should read and enjoy and love—into a discipline problem.”

Early Changes

Knowing something had to change, Thompson decided to try grading students only on whether their participation in class indicated that they had read the book.

“I said, ‘Look. We’re going to read this book, and we’re just going to read it and talk about it. You’re not going to have study questions. You’re not going to have any reading quizzes. But I’m going to know if you read or not. I’m going to know.'”

These early discussions were similar to Socratic Seminar, where students came with questions and Thompson mostly observed. When a student participated in a way that demonstrated that he or she had read the book, their names would be crossed off of a chart. “And that was it,” Thompson says. “The standard says, Be able to read and analyze at grade level. And if they’re doing that, I mean, yeah, cross their name off. Move on.”

For students who scored low on the discussion or who weren’t initially comfortable with active participation, Thompson offered alternative means of assessment. “I said, hey, if I’m wrong with your score, then we need to come up with some sort of alternative: They were used to taking annotations, taking notes on their thoughts while they read—you can show me those. You can sit down and have a conversation just one-on-one, or you can take a test. So if you got an eight out of 10, and you’re like, ‘No, I want the 10 out of 10,’ I have a multiple-choice test on the book.”

Most of the time, Thompson’s initial score on the discussion turned out to be accurate. “I did have a lot of students who had a B for their assessment, and they’re like, No, I want the A. Great. And they took the test and then it was cute, because they were like Yeah, I didn’t really read all of it. So my assessment was, on average, about 3 or 4 percent higher than what they were normally getting on their tests.”

Right away, Thompson started to see changes in how her students were reading. “I had students who started reading more than they were assigned, and they were finishing the book early,” she says. Some were even reading ahead.

Over time, Thompson refined her approach adding small-group time before the large-group discussions, offering scaffolding to help students develop better questions, and structuring student contributions so that the richest questions got the most discussion time.

These changes have so elevated the level of discourse that Thompson sometimes feels like she’s teaching college class. “And that’s exactly what I tell them: ‘What we just did, that was a collegiate literature course. That was amazing. You could walk into a college course and have this discussion.’ And you can see that they’re enjoying it.”

The TQE Method

Here is the approach Thompson uses now, step by step:

1. Students Complete Assigned Reading at Home

Usually, this will be a segment of a longer text, like a few chapters in a novel. Students who show up having not completed the reading are invited to finish up in the hall during small group discussion (step 2) to catch up. They are welcome to return to class for the discussion when they finish.

2. Small Group Discussions (15 minutes)

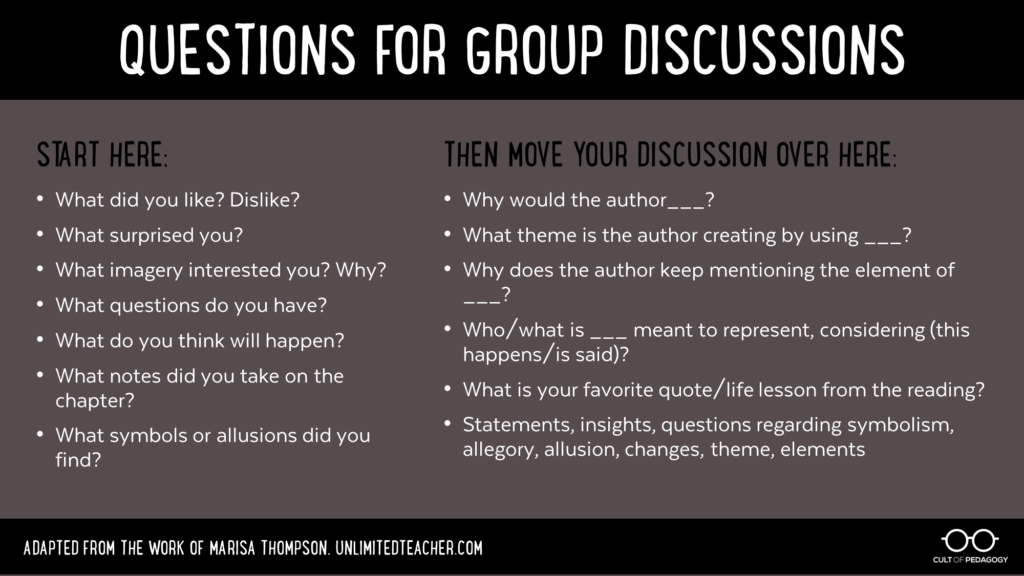

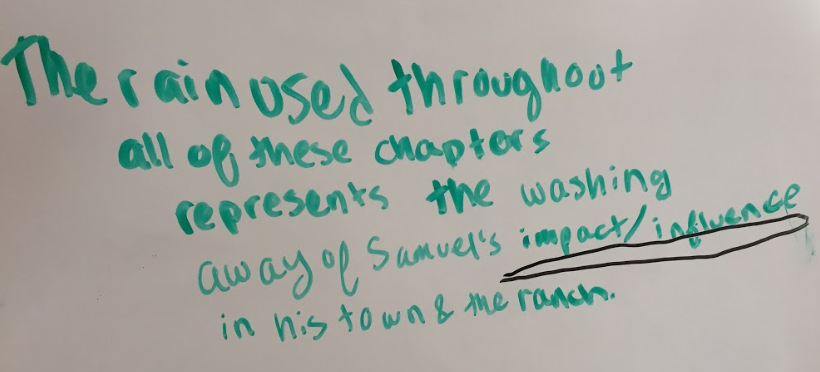

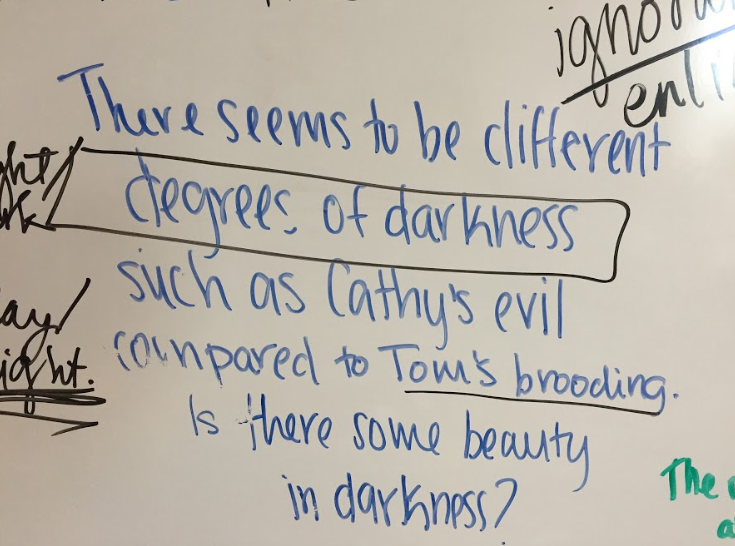

When they arrive in class, students get into small groups, where they have 15 minutes to share thoughts, lingering questions, and epiphanies (TQEs) they have about the reading. Early in the year, Thompson provides stems to help students generate these (see below), encouraging them to move from the more simplistic ideas on the left to the more complex ones on the right.

3. TQEs on the Board

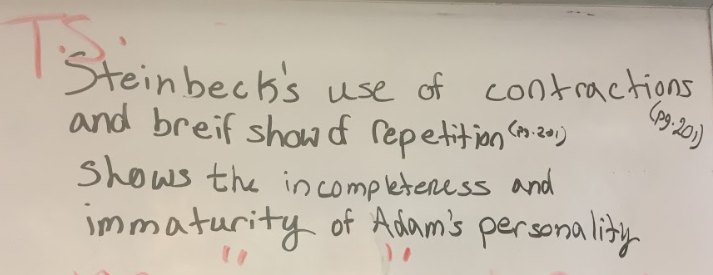

By the time the 15 minutes is up, each group needs to choose their top 2 TQEs from the group and write them on the board. Although these are meant to serve as the basis for the group discussion, they are not necessarily used as is.

“If they put something on there that is not at the quality or as thought-provoking as we need it to be for the class to discuss, we’ll edit it together, the 40 of us,” Thompson explains. “So it becomes a writing lesson.”

Thompson also insists that when discussing a text, students use the author’s name. When discussing Of Mice and Men, for example, she started by having students repeat the name “Steinbeck” five times. “I love Lenny and George. I love Lenny,” she told them. “but he’s totally fictional. So when you start asking questions like, ‘Why did George do that?’ George doesn’t exist.”

Instead, she has students practice asking questions like, “Why did Steinbeck have George do that?” “What theme is Steinbeck trying to convey to the rest of us by having his character do that?”

“It’s not about the character,” she explains. “It’s not about the character’s motivation, it’s the author’s purpose in providing that motivation for the character.”

In small groups, students choose their top two THOUGHTS, lingering QUESTIONS, or EPIPHANIES (TQEs)

and write them on the board for the large-group discussion.

4. Class Discussion of TQEs

Thompson then moderates a whole-class discussion of the reading, using the TQEs that have been written on the board. This takes about 40 minutes of class time—she teaches on a block schedule, so there’s plenty of time to dig in. When the class is actively studying a novel, they will have these conversations in every class meeting.

As for grading, Thompson simply records when students participate, and that’s it. “I have a chart with their little pictures,” she explains, “and I cross them off as I go. So I’m not necessarily grading them every single day. My student Sally might have participated a ton one day, and skipped the next day. But my standard-based grading says she is reading and analyzing at at least grade level. I don’t need to score each of my 40 kids every single day.”

“And the amount of planning is nil,” Thompson adds. “I’m not creating, I’m not copying, I’m not collecting, I don’t need to waste my time. My prep is reading before bed every night.”

What Student-Centered Learning Looks Like

“We have all these really great aphorisms, these quotes about, ‘Students should own their learning,’ and ‘Empower students,'” Thompson observes. “And it’s like, well that’s great, but how in the heck do we do that?”

Since starting the TQE process, Thompson has seen true student-centered learning in action: Students are in charge of the content of the discussions, and the ability to participate fully has become its own motivator for completing the homework.

“The peer pressure of Everyone’s discussing this book—that becomes cool. To have an idea, to have an opinion. So the student comes in, and all of a sudden it’s, “Wait, I read that part, and I think this,” you know? And you want to talk about empowering a student? You just turned that student into a part of the classroom community.”

To read Marisa Thompson’s original blog post about TQEs, click here. To read more of her work, visit her blog at UnlimitedTeacher.com.

Join my mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.