Listen to this post as a podcast:

Sponsored by Peergrade and 3Doodler

Let’s talk about note-taking. Every day, in classrooms all over the world, students are taking notes. I have my own half-baked ideas about what makes one approach better than another, and I’m sure you do too. But if we’re going to call ourselves professionals, we need to know what the research says, yes?

So I’ve combed through about three decades’ worth of research, and I’m going to tell you what it says about best practices in note-taking. Although this is not an exhaustive summary, it hits on some of the most frequently debated questions on the subject.

This information is going to be useful for any subject area—I found some really good stuff that would be especially useful for STEM teachers or anyone who does heavy work with calculations, diagrams, and other technical illustrations. Of course, there’s plenty here for teachers of social studies, English, and the humanities as well, so everyone sit tight because you’ll probably come away with something you can apply to your classroom.

First, Let’s Talk About Lectures

When we think about note-taking, it’s natural to assume a context of lecture-based lessons. And yes, that is one common scenario when a student is likely to take notes. But other learning experiences also lend themselves to note-taking: Watching videos in a flipped or blended environment, reading assigned textbook chapters or handouts, doing research for a project, and going on field trips can all be opportunities for taking notes.

So instead of referring to lectures in this overview, I’ll just talk about learning experiences or intake sessions—times when students are absorbing content or skills through some sort of medium, as opposed to purely applying that content or synthesizing it into some kind of product. Even in student-centered, project-driven classrooms where students pursue their own authentic tasks like the Apollo School, or in more traditional classrooms that set aside time for Genius Hour projects, students need to gather, encode, and store information, so note-taking would still be a fit.

What the Research Says About Note-Taking

1. Note-taking matters.

Whether it’s taking notes from lectures (Kiewra, 2002) or from reading (Rahmani & Sadeghi, 2011; Chang & Ku, 2014), note-taking has been shown to improve student learning. In other words, if we want our students to remember more of what they learn in our classes, it’s better to have them take notes than it is to not have them take notes.

The thinking behind this is that note-taking requires effort. Rather than passively taking information in, the act of encoding the information into words or pictures forms new pathways in the brain, which stores it more firmly in long-term memory. On top of that, having the information stored in a new place gives students the opportunity to revisit it later and reinforce the learning that happened the first time around.

So if you’re not currently having students take notes in your class, consider adding note-taking to your regular classroom routine. With that said, a number of other factors can influence the potency of a student’s note-taking, and that is what these other points will address.

2. More is better.

Although students are often encouraged to keep notes brief, it turns out that in general, the more notes students take, the more information they tend to remember later. The quantity of notes is directly related to how much information students retain (Nye, Crooks, Powley, & Tripp, 1984).

This would be useful to share with students. If they know that more complete notes will result in better learning, they may be more likely to record additional information in their notes, rather than striving for brevity.

Obviously, some students are going to be faster note-takers than others, and this will allow them to take more complete notes. But you can do quite a bit to help all students get more information into their notes, regardless of their natural speed, and that’s what we’ll talk about next.

3. Explicitly teaching note-taking strategies can make a difference.

Although some students seem to have an intuitive sense for what notes to record, for everyone else, getting trained in specific note-taking strategies can significantly improve the quality of notes and the amount of material they remember later. (Boyle, 2013; Rahmani & Sadeghi, 2011; Robin, Foxx, Martello, & Archable, 1977). This is especially true for students with learning disabilities.

One frequently used note-taking system is Cornell Notes. This approach has been around for decades, and the format provides a simple way to take “live” notes in class and condense and review them later.

4. Adding visuals boosts the power of notes.

Compared with writing alone, adding drawings to notes to represent concepts, terms, and relationships has a significant effect on memory and learning (Wammes, Meade, & Fernandes, 2016).

The growing popularity of sketchnoting in recent years suggests that teachers are well on their way to taking advantage of this research.

This video combines sketchnoting with Cornell Notes, and it’s an approach I think is definitely worth considering.

To explore sketchnoting more deeply, check out this list of sketchnoting resources compiled by celebrated education sketchnote artist Sylvia Duckworth.

5. Revision, collaboration, and pausing boosts the power of notes.

When students are given the opportunity to revise, add to, or rewrite their notes, they tend to retain more information. And when that revision happens during deliberate pauses in a lecture or other learning experience, students remember the information better and take better notes than if the revision happens after the learning experience is over. Finally, if students collaborate on this revision with partners, they record even more complete notes and score higher on post-tests (Luo, Kiewra, & Samuelson, 2016).

With this in mind, it would be a good idea to plan breaks in lectures, videos, or independent reading periods to allow students to look over, add to, and revise their notes, ideally with a partner or small group. This partner work could happen after students have had time to revise their notes alone, or students might be given access to classmates for the duration of the pause.

6. Scaffolding increases retention.

Teachers can build scaffolds into their instruction to ensure that students take better notes. One very effective type of scaffold is guided notes (also called skeleton or skeletal notes). With guided notes, the instructor provides some type of outline of the material to be covered, but with space left for students to complete key information. This strategy has been shown to substantially increase student achievement across all grade levels (elementary through college) and with students who present with various disabilities (Haydon, Mancil, Kroeger, McLeskey, & Lin, 2011).

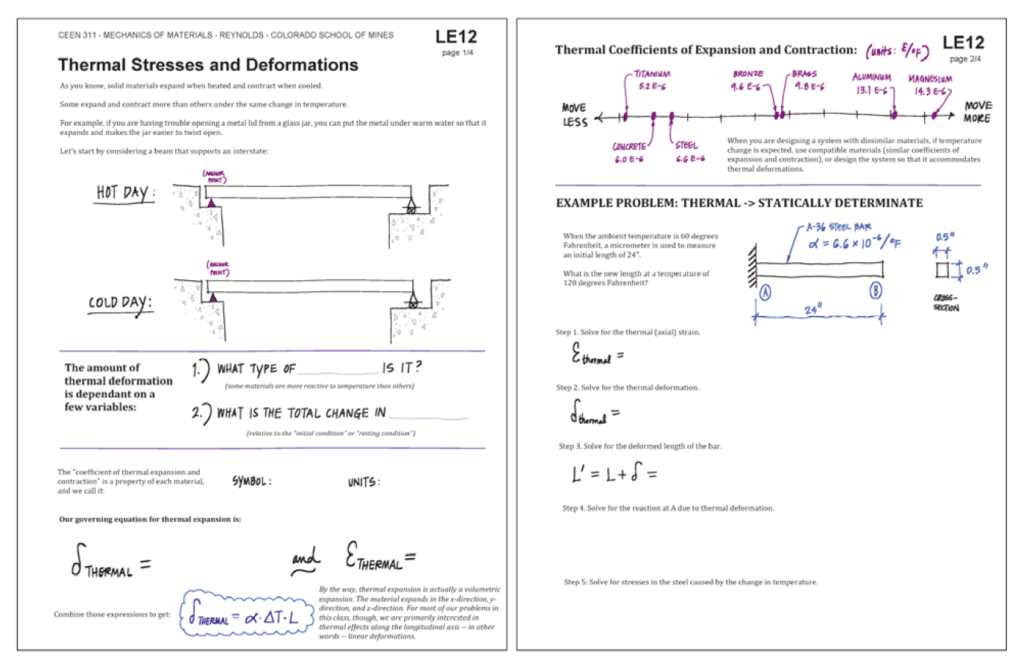

As instructors experiment with guided notes, certain features show a lot of promise. One that I found incredibly interesting was a style developed by engineering professor Susan Reynolds to accompany her lectures: The notes combine typed information, handwritten content, and graphics, but still leave room for student notes and working out example problems.

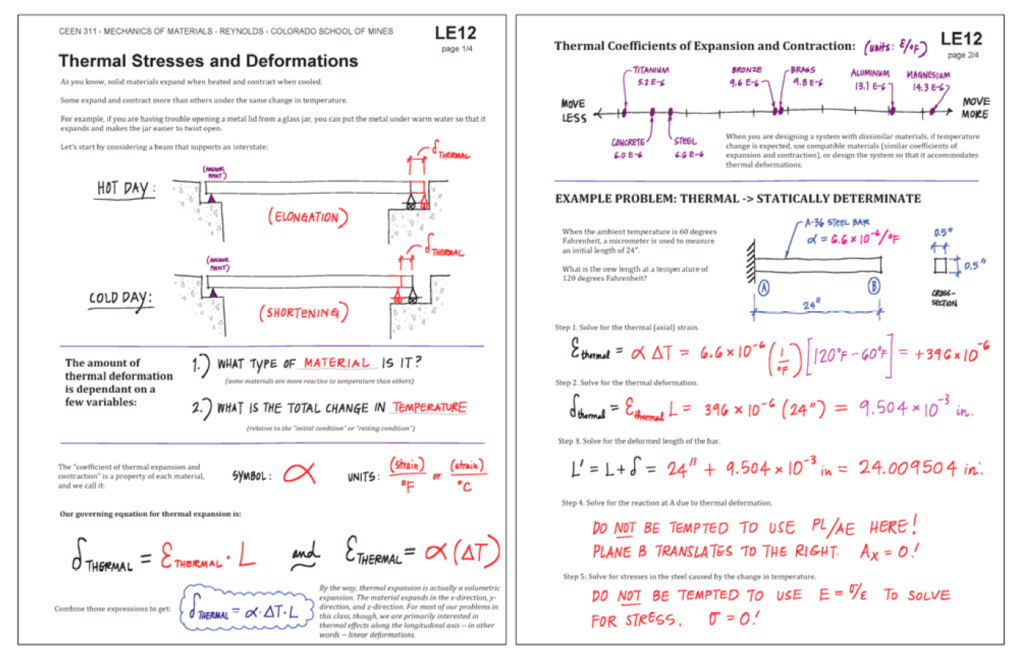

Diagrams are pre-drawn, but some key numbers are left out for students to fill in during the lecture. These notes consolidate all the technical material for a lecture into a single document, and the information is organized to align with the lecture. The more I study these notes, the more I see how useful they are, and how well they balance the efficiency offered by guided notes with the need for students to actively participate in the encoding process.

Guided notes created by engineering professor Susan Reynolds. These have not been completed yet.

The same pages of guided notes completed by the instructor during the lecture.

Reynolds’ students have had strong positive reactions to this style of notes and consistently attribute the notes as a key factor in their engagement and learning in the course (Reynolds & Tackie, 2016).

While teachers should experiment with different styles, the take-away here is that if you want students to get the most out of a learning experience, provide them with some form of partially completed notes.

In the meantime, you can add another layer of scaffolding by simply adding more verbal cues to your learning experiences (Kiewra, 2002). Research shows that simply saying things like, “This is an important point,” or “Be sure to add this to your notes,” instructors can ensure that students include key ideas in their notes. Providing written cues on the board or a slideshow can also help students structure their notes and decide what information to include.

7. Providing instructor notes improves learning.

In an article I wrote a few years ago, I denounced instructor-prepared notes as an ineffective method for teaching, primarily because encoding this information required no effort from students and therefore made the learning too passive.

Although I stand by the assertion that we should avoid simply supplying students with notes, I need to refine the message: Research has shown that when we give students complete, well-written, instructor-prepared notes to review after they take their own notes, they learn significantly more than with their own notes alone (Kiewra, 1985).

If we combine this strategy with student revision, collaboration, and pausing to improve note-taking and learning—in other words, having students pause during an intake session to collaboratively revise their notes, then let them review instructor notes at the end—we can give our students an incredibly powerful learning experience.

One concern is that providing notes might make students more passive about taking their own notes during the learning experience. Here are some suggestions for addressing that:

- Assigning a small grade for student notes would likely compel most students to do them, but this could distort the validity of a grade, as we discussed in another post.

- It would probably be more effective to simply build note-taking into the class activities. For example, if students are encouraged to take notes, and then they are given a pause every few minutes to compare and revise notes, it would be pretty awkward for them to turn to a partner and have nothing to contribute.

- Sharing the research with students that those taking notes then revising them with instructor notes has greater impact than instructor notes alone might push students to take more notes.

- Allowing students to choose a note-taking format that works best for them would also boost student motivation for taking the notes.

8. Handwritten notes may be more powerful than digital notes, but digital note-taking can be fine-tuned.

Studies have shown that students who take notes by hand learn more than those who take notes on a laptop (Mueller & Oppenheimer, 2014; Carter, Greenberg, & Walker, 2017).

This research confirms what a number of educators suspect about the negative effects of digital devices in the classroom, and some have taken it to mean they should definitely ban laptops from their lectures (Dynarski, 2017). Others argue that prohibiting laptop use robs students of the opportunity to develop metacognitive awareness of their own levels of distraction and make the appropriate adjustments (Holland, 2017).

Because technology is always changing, and because as a species, we are still adjusting to these new formats, I would hesitate to ban laptops from the classroom. Here’s why:

- Research on this topic is still pretty young: Some researchers have found no significant difference in performance between paper-based and digital note-takers (Artz, Johnson, Robson, & Taengnoi, 2017). My guess is that more research will pile up and get more refined, so we should take a measured approach for the time being.

- Other researchers are looking at ways to reduce some of the problems associated with digital note-taking, like distraction: One study found that while doing online research, students who used matrix-style notes and were given time limits were much less likely to become distracted by other online material than students without those conditions (Wu, & Xie, 2018).

- I believe we serve our students better by helping them find a note-taking system that works best for them. With that in mind, I would be more likely to have students experiment with hand-written and digital notes, share the research with them, and give them opportunities to reflect on and measure their results.

See What Other Teachers are Doing

To learn more about what other teachers have found to be most effective note-taking methods, I put the call out on Twitter, asking teachers to share what works for them. You can browse that conversation here.

References

Artz, B., Johnson, M., Robson, D., & Taengnoi, S. (2017). Note-taking in the digital age: Evidence from classroom random control trials. http://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3036455

Boyle, J. R. (2013). Strategic note-taking for inclusive middle school science classrooms. Remedial and Special Education, 34(2), 78-90. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0741932511410862

Carter, S. P., Greenberg, K., & Walker, M. S. (2017). The impact of computer usage on academic performance: Evidence from a randomized trial at the United States Military Academy. Economics of Education Review, 56, 118-132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2016.12.005

Chang, W., & Ku, Y. (2014). The effects of note-taking skills instruction on elementary students’ reading. The Journal of Educational Research, 108(4), 278–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2014.886175

Dynarski, S. (2017). For Note Taking, Low-Tech is Often Best. Retrieved from https://www.gse.harvard.edu/news/uk/17/08/note-taking-low-tech-often-best

Haydon, T., Mancil, G.R., Kroeger, S.D., McLeskey, J., & Lin, W.J. (2011). A review of the effectiveness of guided notes for students who struggle learning academic content. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 55(4), 226-231. http://doi.org/10.1080/1045988X.2010.548415

Holland, B. (2017). Note taking editorials – groundhog day all over again. Retrieved from http://brholland.com/note-taking-editorials-groundhog-day-all-over-again/

Kiewra, K.A. (1985). Providing the instructor’s notes: an effective addition to student notetaking. Educational Psychologist, 20(1), 33-39. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep2001_5

Kiewra, K.A. (2002). How classroom teachers can help students learn and teach them how to learn. Theory into Practice, 41(2), 71-80. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4102_3

Luo, L., Kiewra, K.A. & Samuelson, L. (2016). Revising lecture notes: how revision, pauses, and partners affect note taking and achievement. Instructional Science, 44(1). 45-67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-016-9370-4

Mueller, P.A., & Oppenheimer, D.M. (2014). The pen is mightier than the keyboard: Advantages of longhand over laptop note taking. Psychological Science, 25(6), 1159-1168. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797614524581

Nye, P.A., Crooks, T.J., Powley, M., & Tripp, G. (1984). Student note-taking related to university examination performance. Higher Education, 13(1), 85-97. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00136532

Rahmani, M., & Sadeghi, K. (2011). Effects of note-taking training on reading comprehension and recall. The Reading Matrix, 11(2). Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/85a8/f016516e61de663ac9413d9bec58fa07bccd.pdf

Reynolds, S.M., & Tackie, R.N. (2016). A novel approach to skeleton-note instruction in large engineering courses: Unified and concise handouts that are fun and colorful. American Society for Engineering Education Annual Conference & Exposition, New Orleans, LA, June 26-29, 2016. Retrieved from https://www.asee.org/public/conferences/64/papers/15115/view

Robin, A., Foxx, R. M., Martello, J., & Archable, C. (1977). Teaching note-taking skills to underachieving college students. The Journal of Educational Research, 71(2), 81-85. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.1977.10885042

Wammes, J.D., Meade, M.E., & Fernandes, M.A. (2016). The drawing effect: Evidence for reliable and robust memory benefits in free recall. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 69(9). http://doi.org/10.1080/17470218.2015.1094494

Wu, J. Y., & Xie, C. (2018). Using time pressure and note-taking to prevent digital distraction behavior and enhance online search performance: Perspectives from the load theory of attention and cognitive control. Computers in Human Behavior, 88, 244-254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.07.008

Join my mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.