Listen to my interview with Jen Serravallo (transcript):

Sponsored by Peergrade and Microsoft Inclusive Classroom

This post contains Amazon Affiliate links. When you make a purchase through these links, Cult of Pedagogy gets a small percentage of the sale at no extra cost to you.

A few weeks ago, a teacher named Isabelle O’Kane sent me a direct message on Twitter. She had been reading a debate that was raging all over social media, and she wondered if it was something I might want to write about. The debate took place in response to a single tweet sent out by literacy experts Irene Fountas and Gay Su Pinnell:

The classroom library should NOT be organized according to level, but according to categories such as topic, author, illustrator, genre, and award-winning books. #FPLiteracy pic.twitter.com/hxJNDow3Qz

— Fountas & Pinnell (@FountasPinnell) September 21, 2018

Teachers responded to the tweet from all directions: Some shouted hallelujah, because it supported what they were already doing. Others agreed, but argued that their hands were tied because administration required leveled libraries. Quite a few insisted that the best approach was to do both; yes, students should be able to seek out books based on interest, but without levels, how would they ever find appropriate books on their own? And some threw up their hands entirely, wondering if a single, clear answer was ever going to present itself.

Because my training and classroom work has all been with students in grade 6 and above, I don’t have a lot of experience or knowledge on this topic, but it definitely seemed like something teachers needed help with.

Jennifer Serravallo

So it was pretty serendipitous when literacy consultant and author Jennifer Serravallo contacted me right around that time about her new book, Understanding Texts & Readers: Responsive Comprehension Instruction with Leveled Texts.

In the book, Serravallo takes a deep dive into the question of how best to match texts to readers. She starts with a discussion of why we have leveled texts to begin with, what their original purpose was, and the missteps we often make as teachers when using them. Then she explores the levels themselves—for fiction and non-fiction—and unpacks the characteristics to look for in each one. Finally, she brings it all together, showing teachers how to combine their knowledge of text levels and students to assess student comprehension, set goals, and match students with books that are just right for them.

In our conversation, which you can listen to on the podcast player above, we talked about the mistakes a lot of teachers and administrators make in how they use leveled texts, and what they should be doing instead.

What Are Leveled Texts?

When schools first attempted to differentiate reading instruction, they did it with texts that were written specifically for that purpose, like the SRA cards that were popular in the 1960s and 70s. Although these programs offered different levels to match student readiness, “(they didn’t) actually offer kids real language structures or really interesting storylines,” Serravallo explains. “And kids were not able to read those with as much comprehension as real children’s literature.”

In the 1990s, a shift came when teachers started looking at ways to level real books, books that were not written with “levels” in mind. Two types of text leveling emerged around this time:

Quantitative Leveling: Systems like the Lexile Framework leveled texts through computer programs that measured dimensions like text length and complexity.

Qualitative Leveling: This type of leveling is done by humans, and while it considers things like text length and complexity, it also takes more nuanced qualities into consideration, like whether a text delivers information in a purely straightforward way or contains multiple levels of meaning. One popular qualitative system is Fountas and Pinnell’s Text Level Gradient.

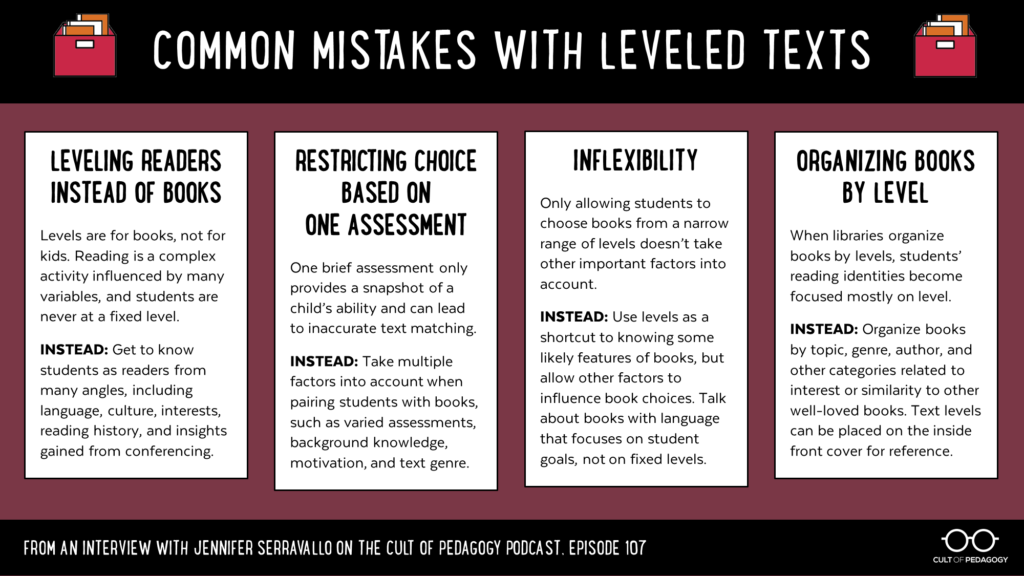

Common Mistakes with Leveled Texts

When leveled texts are used in classroom and school settings, teachers and administrators make some well-intentioned but significant missteps that can negatively impact students’ growth as readers.

1. Leveling Readers Instead of Books

One of the biggest mistakes Serravallo sees is labeling students by text levels. “Levels are meant for books, not for kids,” she explains. “There’s really no point in time when a kid is just a level, just one. There’s a real range, and it depends on a lot of other factors.”

This misstep, she says in her book, has had negative consequences. “Kids nationwide have become aware of something that many would argue they shouldn’t be aware of at all…causing some students to compete, race through levels, and experience shame.”

To compound the problem, a number of schools have begun basing student learning objectives (SLOs)—part of teacher evaluation protocols—on these levels: “(Districts will) say, ‘You come up with goals for your students, and then we’re going to measure and make sure you met your goals.’ And what’s happening is that I find teachers are using levels (to measure growth)—’This student’s starting off at an L and is going to end up at a P,’ or something like that.”

This type of system often prompts teachers to put books in students’ hands that they’re not quite ready for. “The teacher is going to be pushing the student into harder texts in order to meet the goal,” Serravallo says. “You’ve got this kid being pushed through because they can maybe decode the text but not because they’re actually getting everything they can from it in terms of comprehension and meaning making. If the kids are not thinking on that level, why be pushing them into harder and harder books? Why not work with them in texts that they choose to help them get more from the texts that they’re reading?”

What to do instead: Rather than focus narrowly on text levels, teachers should get to know students as readers from a variety of angles. “Factors such as motivation, background knowledge, culture, and English language proficiency should all be on our radar when considering how to help students find books they’ll love, and how to evaluate students’ comprehension and support them with appropriate goals and strategies.”

2. Restricting Book Choice Based on a Single Assessment

“One of the ways that levels get misused is that teachers administer one assessment,” Serravallo says. “It’s usually a short assessment. It could be a computer assessment that’s a short text with multiple choice, it could be a running record where kids read a selection of a text and answer a few questions. So there’s this one assessment, and then from that they get a level or a level range, and they say to the kids, you can only pick from that level range. But the problem is that’s misunderstanding all of the different variables that kids bring to the table, things like motivation, prior knowledge, stamina, their command of English, the genre. There’s so many variables.”

What to do instead: Take multiple factors into account when pairing students with texts. “We need to look at a couple of different assessments,” Serravallo recommends, “and we need to account for these variables, and then once we have a sense of about where kids are able to read, we still need to be flexible when they go to choose. So if I have a kid who knows a lot about dinosaurs who typically reads books around Level O-P, if it’s a dinosaur book and he wants to read it, and it’s a Level R or S, maybe that’s okay.”

3. Inflexibility

Even if we have a pretty thorough idea of what types of texts would be a good fit for a student, only allowing them to choose books from a narrow range of levels doesn’t take other important factors into account. There may be times when a student wants to challenge herself by going for a book that will require more support to get through, and other times when students want to read an easier book for fun.

“Saying to a student, ‘You are a Level __ so you can only read Level __ books’ is deeply problematic,” Serravallo writes in her book. “We can use reading levels to help guide student choice, but levels should never be used to shackle a reader.”

What to do instead: Use reading levels as a shortcut to knowing some likely features of books, but allow other factors to influence book choices. In her book, Serravallo shows us how to adjust our language to help students make these decisions for themselves: Instead of saying something like, “That book is too hard for you,” she recommends saying something like, “That book is harder than what you typically read. Let’s think about how I/your friends can support you as you read, if you find you need it.”

4. Organizing Books by Level

While Serravallo admits to organizing the books in her classroom library in leveled bins years ago, “I’ve changed my thinking after seeing the consequence of what that does to kids’ reading identity. What ends up happening is kids go to the classroom library and they say, ‘I’m a Q. I’m going to pick a Q book.’ And they go to the Q bin and they only look in the Q bin.”

What to do instead: “I would organize them by topic, by genre, by author,” Serravallo says, “So the first thing kids see when they go to the library is identities. And they think about themselves first before they think about level: Who am I as a reader, and what am I interested in reading?”

For her own purposes, Serravallo would still keep text levels on books, but put them in an inconspicuous place on the book, like on the inside of the front cover. “That way, when a child is holding a book, it’s not like everyone can see the level on the book, so it’s a little bit more private. But I like that having them on the book, because if I haven’t read that book, I can peek at the level and be like, oh yeah, okay. Complex characters in this one. And I can use that to guide my discussions when I’m working with kids.”

To learn more, check out Serravallo’s book Understanding Texts and Readers, join the Reading and Writing Strategies Community on Facebook, or visit her website at jenniferserravallo.com.

Join my mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.